Three-quarters of new and emerging infectious diseases in humans originate in wildlife. COVID-19, SARS and Ebola all started this way. The COVID-19 global pandemic has drawn new attention to how people think about wild animals, consume them and interact with them, and how those interactions can affect public health.

Any activity that puts people in close proximity to disease-prone animals is risky, including wildlife trade and the destruction of natural habitats. In response to the current pandemic, China and Vietnam have instituted bans on wildlife consumption. Global leaders and U.S. policymakers are calling for a ban on wildlife markets worldwide.

We study global environmental governance and human security. As we see it, banning the wildlife trade without action to reduce consumer demand would likely drive it underground. And curbing that demand requires recognizing that much of it comes from wealthy nations.

A complex and mostly legal trade

Global commerce in wildlife affects billions of animals and plants, and operates through both legal and illegal channels. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates the value of the legal trade at US$300 billion annually. TRAFFIC, a leading nongovernmental organization, estimates that the illegal wildlife trade is worth $19 billion annually. Illegal wildlife trafficking is one of the largest drivers of transnational crime worldwide.

Discussions about wildlife consumerism often ascribe consumption to a false, all-encompassing archetype of an “Asian super consumer” with “weird” appetites for exotic animals. This perspective focuses on newly wealthy Asians who want to buy ivory, rhino horn or, more recently, pangolin.

Another common trope depicts poachers as male, greedy, gun-toting African criminals. In fact, poaching and hunting for “bush meat,” or meat from wild animals, are more often symptoms of poverty and a lack of other income-generating opportunities.

These false stories can result in blinkered policy decisions that ignore the real motivations driving both consumption and poaching. In particular, consumer demand in the United States and Europe is a significant driver of wildlife trade. And wildlife products appeal to Western consumers for many of the same reasons that drive demand in other parts of the world.

The roles of gender, class and culture

According to a 2017 study, between 2000 and 2015 the United States imported more than 5 million shipments of live and dead wildlife. They included mammals, birds, fish and reptiles purchased as exotic pets, along with timber, plants and animal parts. The number of shipments declared each year more than doubled between 2000 and 2015.

Consumption reflects social values, and consumer preferences vary by culture, class and gender. What do a 150-ounce steak in the United States and tiger penis wine in China have in common? The culturally symbolic belief that they exemplify and promote male virility. Similarly, luxury wear items – such as exotic giraffe leather boots in Texas, python skin jackets in Milan and fur coats in Florida – are a way of dressing to impress others.

What people consume and how is influenced by socially conditioned roles and responsibilities, reinforced by television and advertising. Conceptions of gender most often determine the perceived value of the product and shape consumption preferences.

For example, products like fish swim bladder – also known as aquatic cocaine – and cosmetics containing shark liver oil appeal to perceptions of female beauty, targeting aging women with false promises of eternal youth. In Asia, ground pangolin scales are marketed as a treatment for lactation problems. Trophy hunters’ photographs and showrooms with taxidermied lions or elephant tusks appeal to perceptions of masculinity.

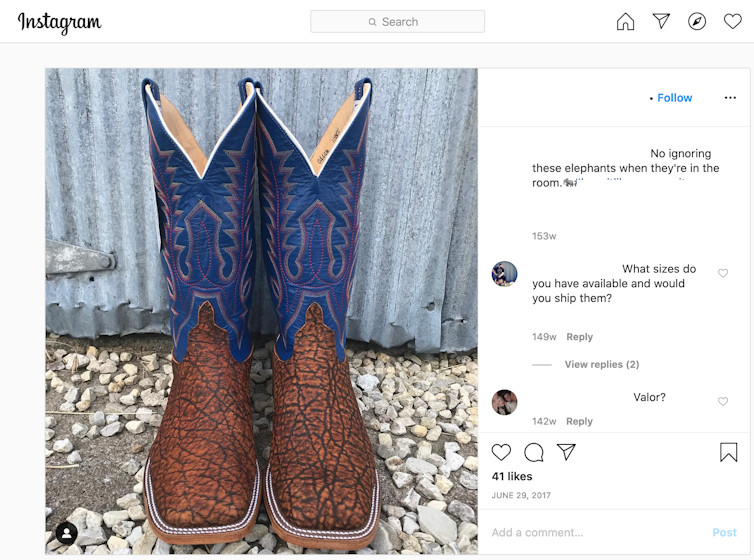

Poaching of elephants for ivory has received wide coverage in Western media, but their skins turn up in boots that are legally marketed in wealthy nations. Giraffe skins are also legal goods that may be sold as expensive décor, boots or Bible covers. U.S. demand for boots sheathed with the scales of pangolins – the world’s most-trafficked mammal and a suspected source of COVID-19 – has contributed to this species’ decline.

Performing a quick online search, we identified more than 30 retailers selling elephant leather products in the United States, mainly exotic boots. Their ads promote virility — “Just a hard-working, tough as nails, pair of American made cowboy boots” — and promise that others will be impressed, with messages like “No ignoring these elephants when they’re in the room.”

From Instagram

Targeting the fashion industry

Western countries mostly import wildlife goods, which can make the effects of this trade seem far removed. However, media exposés are making it hard for wealthy consumers and businesses to deny its impact.

While many question whether Asians will stop eating wild animals, we question whether Western consumers will stop wearing them. The global fashion industry, with an estimated annual valuation of US$3 trillion, is an important target for change.

Some companies have responded to campaigns by advocacy groups like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, which has crashed runways and solicited celebrities. PETA has claimed victory for its 30-year campaign, “I’d Rather Go Naked Than Wear Fur.” “Nearly every top designer has shed fur, California has banned it, Queen Elizabeth II has renounced it, Macy’s is closing its fur salons, and now, the largest fur auction house in North America has filed for bankruptcy,” said PETA senior vice president Dan Mathews when the campaign ended in 2020.

Still, the industry has far to go. “Despite some modest

progress, fashion hasn’t yet taken its environmental responsibilities

seriously enough,” the consulting firm McKinsey observed in a recent report, noting that many younger consumers were demanding “transformational change.”

Now animal welfare advocates are focusing on leather and wool production. Fashion houses including Chanel, Nine West and Victoria Beckham are banning the use of exotic leathers. California has also banned them from being sold.

Many brands source fur, feathers and skins from factory farms that raise exotic species and legally trade captive-bred endangered species that are illegal to source from the wild. The absence of strong regulatory measures allows for illegally obtained skins to be passed off as legal.

Better quality control of fashion materials could make it harder for companies to work with these suppliers. Learning from seafood industry systems that trace products from origin to consumption could ensure transparency and bring order to complex supply chains.

Changing consumer preferences

Ultimately, reducing demand for wildlife products will require regulation as well as educating consumers about the consequences of their choices. Helping people understand the harmful impacts of products ranging from plastic bags and plastic straws to gasoline-powered cars is the first step in persuading them to consider alternatives. And when they do, and policies change, producers listen and shift supply.

We see targeted campaigns as an effective way to unearth consumption biases and mobilize action for public and planetary health. In our view, more brands and designers banning wildlife products, and greater peer pressure for behavior change, will promote more sustainable consumption patterns that benefit both humans and wildlife.![]()

Maria Ivanova, University of Massachusetts Boston and Candace Famiglietti, University of Massachusetts Boston

Maria Ivanova, Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director, Center for Governance and Sustainability, John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston and Candace Famiglietti, Doctoral Student, Global Governance and Human Security and Research Associate, Center for Governance and Sustainability at John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/