At a time of heightened polarization and intense inequality in the United States and around the world, social differences run the risk of being turned into fault lines, and exploited for divide-and-conquer politics. As political scientists Rose McDermott and Peter K. Hatemi recently observed, inflammatory us-versus-them rhetoric “instigates neural mechanisms from the evolutionary desire to be part of the group.”

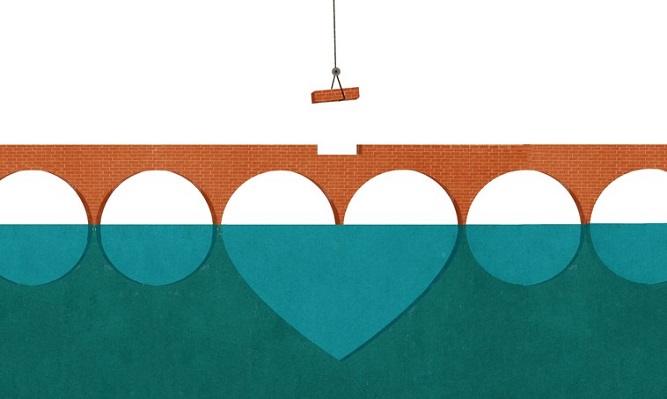

Diversity can be a great strength, but it is susceptible to manipulation when not accompanied by community leaders from all backgrounds willing and able to bridge across difference. The idea of “bridging” provides a path to healing the practices of “breaking” across communities of difference that are so prevalent today.

Now used more broadly, bridging originates in social capital theory. It’s a concept used to investigate trust and social cohesion, as well as reciprocity and civic bonds. It describes relationships between and among different groups of people in society, and is a form of social capital, which examines connections that connect people across a cleavage that often divides society (such as race, class, or religion). Bridging occurs when members of different groups reach beyond their own group to members of other groups. Examples of this would be moving into integrated neighborhoods or joining sports clubs or places of worship where people hold different identity markers from oneself.

Several years ago, here at the University of California, Berkeley, we began to examine bridging through the lens of “othering and belonging.” “Othering” occurs when a person or group is not seen as a full member of society, as an outsider or “less than” or inferior to other people or groups. It happens at an interpersonal level across many dimensions such as race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, and others, but is also expressed at the group level. When governments and other elites participate in the othering of certain groups, othering reaches its most dangerous level, and can lead to violence, and even genocide.

One of the mechanisms of othering is the practice of breaking—the antithesis of bridging. Breaking occurs when members of a group not only turn inward (known as “bonding,” in social capital terms), but also turn against the “outsider” group or the other. The otherness and threat of the out-group can be used to build psychological or physical walls. It tells the other, “You are not one of us. You don’t belong and you should not get the same public resources or attention and regard that my group gets.” Breaking emerges from a belief that people who are not part of the favored group are somehow dangerous or unworthy. It is largely based on fear, and a feeling of insecurity. These emotions may be grounded on a belief that “those people”—whoever they are—are stealing our jobs, harming our neighborhoods, or that they pose a threat to our sacred values and norms.

In the U.S. political environment today, there are multiple “others.” Immigrants, Muslims, and people of color are prominent “others,” and our current administration advances breaking policies and employs divisive rhetoric that enflames fear of these others. But even well-meaning liberals undermine bridging and perpetuate othering through strategies such as assimilation.

For example, the notion of “not seeing difference” or assuming that one group is just like another, more favored group, can undermine the building of bridges. Saying that “Muslims are just like Christians even though they attend a mosque instead of a church” erases any differences, and tries to assimilate the marginalized group into the dominant one.

Meaningful bridging—such as real integration—must acknowledge, respect, and appreciate difference as a starting point, not try to erase differences. Bridging requires more than just acknowledging the other but listening empathically and holding space for the other within our collective stories. This, of course, is not easy. As author bell hooks reminds us, bridges get walked on.

There are different types of bridges. Short bridges require less effort, less risk, and less vulnerability to erect. Longer bridges are those that require more of us and our communities. They entail greater risk, but also greater reward.

To bridge requires strength and empathy, but it does not require that we sacrifice our values or our identity. It also entails vulnerability, as when Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern responded to New Zealand’s mass shooting by affirming values of diversity, refuge, and compassion.

Bridging is so important because only bridging can heal a world of breaking, which is the dominant practice and discourse today. Breaking not only feeds off broad-scale social changes and polarization, it also propels them.

By imagining together, we can use bridges to hear the other and help construct a larger more inclusive “we” where no group dominates or is left out.