Mary Estrada, 56, met her husband, Robert, when she was 10 years old and he was 9. They have been together most of their lives, but they have also spent many years physically apart.

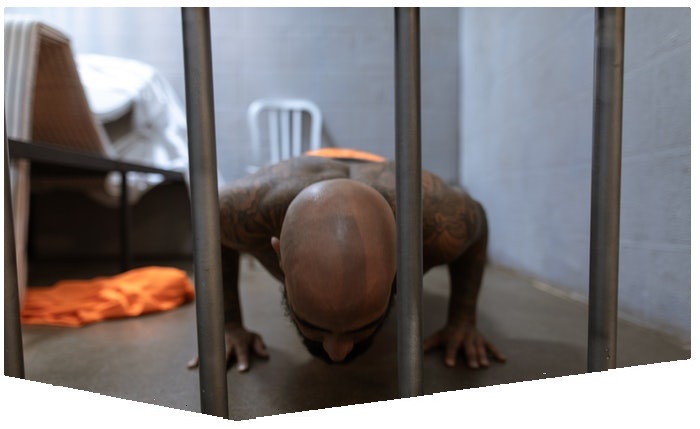

Robert Estrada’s contact with the criminal legal system began early, with time in the city’s juvenile detention facility that ignited a cycle of incarceration. Currently he is serving a 52-year sentence at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility in San Diego, more than two hours from Estrada’s home in Pomona, California.

Over the decades, Estrada said she has remained her husband’s steadfast support system. Every weekend she drives 135 miles each way to visit Robert. She talks to him on the phone at least once a day, sometimes twice, at a rate of about $2 for 15 minutes. She makes sure to keep money on his account at the prison so that he can buy things he needs. Estrada also recently paid off his $10,000 restitution fees.

“If I can go back all the way to 18 years old, I’d be a billionaire with all the money that I’ve spent just following him and just, you know, being with him,” Estrada told The 19th. “It’s been a hard journey. It’s been a long journey. And I mean, you just have to keep going forward. I love him.”

Estrada’s experience is one familiar to many women with incarcerated romantic partners, co-parents or family members. An estimated 1 in 4 women in the United States have a family member in prison, according to the Essie Justice Group, a California-based nonprofit that advocates for women with incarcerated loved ones. Black, Latinx and low-income people are more likely to know someone who has come into contact with the criminal legal system.

A new report co-authored by Essie and the Prison Policy Initiative, a research nonprofit, gives more insight into what California counties and neighborhoods are hit hardest by incarceration. According to their analysis published in late August, high incarceration numbers can be traced to more expected urban areas such as Los Angeles County, where Estrada and her husband are from, as well as a number of much smaller counties.

Overall, Los Angeles County has an imprisonment rate of 402 per 100,000 residents, but it is the highest – approximately 773 to 1,093 per 100,000 residents – in the neighborhoods of South Central L.A., where 57 percent of residents are Latino and 38 percent are Black.

Urban counties like Los Angeles send the largest number of people to prison due to the more dense population. Communities of color in particular are more likely to experience poverty, lack of investment, overpolicing and racial profiling that contribute to mass incarceration.

High imprisonment rates exact a toll on those communities, both emotionally and economically. Given that about 93 percent of incarcerated people are men, and about half are fathers, many women are left to manage families without their loved ones.

“I think what is a bit less obvious to people is all the costs that are associated with incarceration, and how women disproportionately share or the burden of those costs of their loved ones,” said Kristin Turney, a sociology professor at the University of California, Irvine.

At one point, for instance, Estrada, who works as an accountant, was spending close to $2,000 a month to help her husband. That amount was on top of what she spent each month on her own housing, food, commuting and child care, she added. That’s money that could have gone toward her family, her savings, or her community.

The Estradas’ 32-year-old daughter also felt the toll. Robert has been incarcerated for most of her life. Mary Estrada recalled asking her daughter what she remembers about her childhood. Her daughter’s response was “nothing,” followed by her recollections of being taken to see her dad two hours away every weekend.

For women and children generally, Turney’s research indicates that the accumulation of these various challenges can lead to further economic hardship for women who are already more likely to be low income. It also leads to increased stress and mental health challenges that can affect physical well-being as well.

These stresses affect families well beyond the Los Angeles metro area, the analysis shows. Several smaller, more rural California counties have disproportionately high imprisonment rates. Kings County, which is home to fewer than 200,000 people, has the highest imprisonment rate of any county in the state with 666 people in state prisons per 100,000.

“The notion of mass incarceration as a problem of big cities: That’s a myth,” said Mike Wessler, the communications director for the Prison Policy Initiative. “When you sit back and think about what’s going on in a lot of these rural communities you realize that a lot of the challenges— things like a lack of economic opportunity, untreated mental health issues, addiction issues – a lot of them are similar to those happening in bigger cities as well.”

The high incarceration rates among rural areas in California mirror national trends. In fact, the jump in incarceration rates among women in particular has been fueled by the country’s smallest counties.

The Essie Justice Group and Prison Policy Initiative’s breakdown of the state’s California imprisonment rates was possible due to recent changes in how the state reports its incarcerated residents.

The majority of states count incarcerated people as residents of the counties where they are imprisoned, rather than the counties where they came from. This can funnel political power away from communities of color when states redraw their congressional and legislative maps, which they do every 10 years based on Census data.

California is one of about a dozen states around the country that has ended this “prison gerrymandering” and counts incarcerated people as residents of the counties they came from. The Prison Policy Initiative has partnered with other organizations in each of these states to produce reports on Nevada, Colorado, Washington and Virginia, among others.

Having this data available will allow researchers, lawmakers and advocacy to get a more complete picture of historic investments or disinvestments in certain areas, Wessler said. It will also highlight regions in need of more resources for formerly incarcerated people trying to reenter society.

“We know where people who have been incarcerated are most likely to return to, so where can states and local governments invest dollars to make sure that when somebody leaves prison, they’re able to find a home, find a job and build communities that support connection?” Wessler said. “We know that without those things, people are much more likely to end up behind bars again.”

Estrada said she wants to see more women like her, the romantic partners and family members of the incarcerated, also get more support. She is currently the administrator for a Facebook group called CDCR: Families and Loved Ones of the Incarcerated, which has helped her find some community and understanding.

While some women may choose to leave romantic relationships with an incarcerated person, many, like Estrada, choose to stay for a multitude of reasons that can include feeling more bonded to their partners through the experience, Turney said.

Despite the difficulties Estrada has faced over the years, she believes she’s “destined” to be with Robert. “I wouldn’t trade him in. I love him,” she said. “I don’t see my thoughts with anybody else. Only him. Even doing this journey, you know, it only makes us stronger.”

Originally published by The 19th