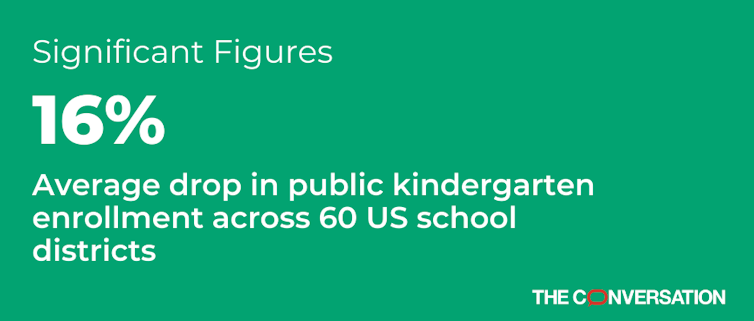

Delaying children’s kindergarten entry is not new, but the pandemic has broadened its scope. And that has the potential to exacerbate already wide educational inequities. As a child and family policy researcher and a parent of two children under 7, I believe the new trend is concerning.

Why enrollment dropped

In a typical year, about 5% of kindergarten-age children are “redshirted” – their entry to school delayed. The phrase originally referred to college athletes who were held back from competing on varsity teams. Parents might delay kindergarten until their children are more socially, emotionally and physically mature.

Research suggests that this extra year before entering school may improve children’s attention and self-regulation. But the academic benefits of redshirting seem to decline as children age into middle and high school.

The reasons for kindergarten delay this past year, however, are unique to the pandemic.

Many families have no in-person school option and may be understandably wary of the effectiveness of online learning, especially for younger children. Parents have long heard from the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Psychological Association and other groups about the harms of too much screen time, and so some may have opted to avoid it for their children’s schooling.

And, virtual learning simply can’t offer the interactions with toys, physical games, peers and teachers that young children need to build foundational skills like compromise.

Many parents are also incredibly stressed as they try to balance work and family demands – now 10 months into the pandemic. Managing children’s Zoom schedules, organizing learning materials and overseeing at-home assignments adds to an already overflowing plate. The problem is worse for parents who cannot work from home and are left with few child care options.

For families with in-person or hybrid schooling options, public health measures like masks and social distancing make kindergarten a less welcoming environment. And, of course, health concerns about catching the coronavirus have led more families to keep their children home this year.

Impact on learning and equity

In a typical year, boys, white children and children from high-income families are most likely to be held back. However, this year school enrollment is down disproportionately among Latino and Black children. This compounds the inequitable access to in-person schooling.

One survey found that half of Latino, Black and single-parent families had fully remote schools compared to a third of white families. Moreover, limited internet and device access also contributes to inequities in remote learning.

What widespread delays in kindergarten enrollment means for children’s learning depends on how they are spending their time when they are not in public school. Some children, especially those from high-income families, are attending private schools, which are more likely to offer in-person schooling. An increasing number of families are choosing to home-school.

But for some children, economic insecurity, material hardship and increased stress at home can change family dynamics and lead to fewer opportunities for learning.

These pressures are even higher for the families – disproportionately those of color – who face personal or family illness, unemployment or smaller paychecks. A recent report by the Urban Institute found that in September 2020, four in 10 Latino and Black families reported food insecurity, compared to 15% of white families – all historically high figures.

Inequities in children’s kindergarten experiences compound inequities in early childhood experiences. Research consistently shows the benefits of early childhood education for children’s development. But access to early learning opportunities has become even more inequitable in the pandemic, according to a report from the Center for American Progress.

These inequities exacerbate the already wide racial, ethnic and socioeconomic achievement gaps. For example, recent evidence suggests that children’s progress in math is down, and more so among children in low-income communities. Many young children are not meeting the benchmarks for early literacy and numeracy skills, which puts them at risk for long-term academic problems.

Impact on schools

When schools eventually reopen full-time, teachers will have to teach to a wider range of skills and needs among their students as a result of these widening achievement gaps. And, it’s likely that the kindergarten class of 2021-2022 will be larger than normal, creating hassles around class sizes, space and staff needs.

For now, the lower enrollment hurts public school budgets.

Schools typically receive public funds based on a per-child allotment that depends on child enrollment and attendance. With enrollment and state and local revenues down, spending on K-12 schools is estimated to decrease as much as 10% in the 2021 fiscal year. In the long term, public schools may face permanent decreases in enrollment as some families opt to remain in private school or keep homeschooling.

Decreased funds come at a time when schools’ costs are up. Schools have had to train teachers in virtual learning and expand health and safety measures, like upgrading ventilation systems and hiring more staff for smaller classrooms.

Public schools will need more financial relief to recover. The December 2020 COVID-19 relief package includes US$54 billion for K-12 public education, although it might not be enough to fully repair the damage from the pandemic.

Given the pressures on families, combined with hopeful news about vaccines, it’s not surprising that parents are choosing to wait until next year to send their children to school. While we won’t know the full impact on children’s learning or school budgets for years, fewer children in kindergarten now is likely to have long-term, cascading consequences for everyone.![]()

Taryn Morrissey, American University School of Public Affairs

Taryn Morrissey, Associate Professor of Public Administration and Policy, American University School of Public Affairs

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.