FDA approval of over-the-counter Narcan is an important step in the effort to combat the US opioid crisis.

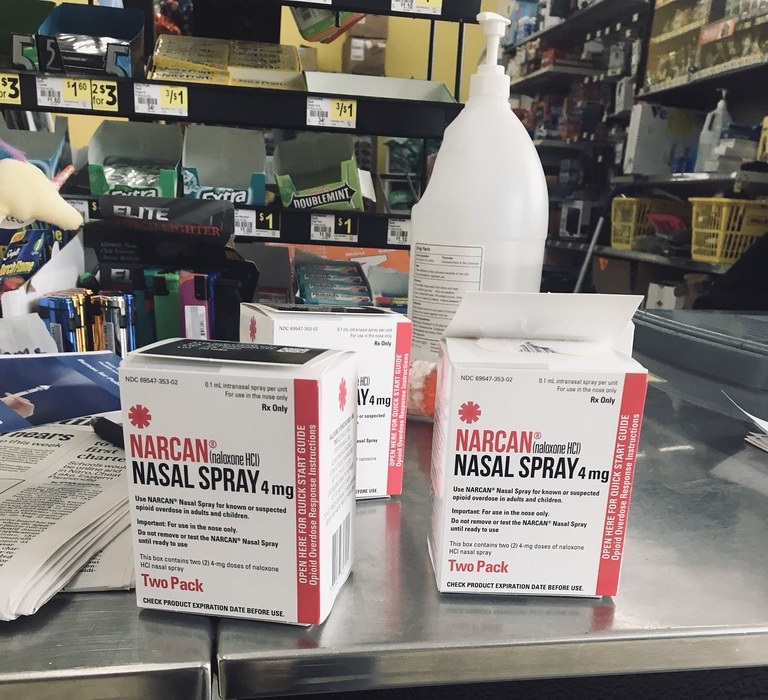

On March 29, 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Narcan for over-the-counter sale. Narcan is the 4-milligram nasal spray version of naloxone, a medication that can quickly counteract an opioid overdose.

The FDA’s greenlighting of over-the-counter naloxone means that it will be available for purchase without a prescription at more than 60,000 pharmacies nationwide. That means that, for 90% of Americans, naloxone nasal spray will be accessible at a pharmacy within 5 miles from home. It will also likely be available at gas stations, supermarkets and convenience stores. The transition from prescription to over-the-counter status is expected to take a few months.

We are pharmacists and public health experts who seek to increase public acceptance of and access to naloxone.

We think that making naloxone available over the counter is an essential step in reducing deaths due to overdose and destigmatizing opioid use disorder. Over-the-counter access to naloxone will permit more people to carry and administer it to help others who are overdosing. Moreover, increasing naloxone’s over-the-counter availability will convey the message that risks associated with substance use disorder warrant a pervasive intervention much as with other illnesses.

Deaths from opioid overdoses across the U.S. have increased nearly threefold since 2015.

Between October 2021 and October 2022, approximately 77,000 people died from opioid overdoses in the U.S. Since 2016, the synthetic opioid fentanyl has been responsible for most of the drug-involved overdose deaths in America.

What is naloxone?

Naloxone reverses overdose from prescription opioids like fentanyl, oxycodone and hydrocodone and recreational opioids like heroin. Naloxone works by competitively binding to the same receptors in the central nervous system that opioids bind to for euphoric effects. When naloxone is administered and reaches these receptors, it can block the euphoric effects of opioids and reverse respiratory depression when opioid overdose occurs.

There are two common ways to administer naloxone. One is through the prepackaged nasal sprays, such as Narcan and Kloxxado or generic versions of the drug. The other method is via auto-injectors, like ZIMHI, which deliver naloxone through injection, similar to the way epinephrine is delivered by an EpiPen as an emergency treatment for life-threatening allergic reactions.

The FDA will review a second over-the-counter application for naloxone auto-injectors at a later date. Although no interaction with a health care provider will be needed to purchase over-the-counter naloxone, when naloxone is purchased at a pharmacy, a knowledgeable pharmacist will be able to help people choose a product and explain instructions for use.

Research shows that when people who are likely to witness or respond to opioid overdoses have naloxone, they can save patients’ lives. This also includes bystanders as well as first responders like police officers and paramedics.

But until now, people in those situations could intervene only if they were carrying prescription naloxone or knew where to retrieve it quickly. Friends and family of people who use opioids are often given prescriptions for naloxone for emergency use. Over-the-counter naloxone will help make the drug more accessible to members of the general public.

Reducing stigma and saving lives

Naloxone is a safe medication with minimal side effects. It works only for those with opioids in their system, and it’s unlikely to cause harm if given by mistake to someone who’s not actively overdosing on opioids.

Since approximately 40% of overdoses occur in the presence of someone else, we believe public access to naloxone is extremely important. People may wish to have naloxone on hand if someone they know is at an increased risk for opioid overdose, including people who have opioid use disorder or people who take high amounts of prescribed opioid medications.

Community centers and recreational facilities may also keep naloxone on hand, similar to the placement of automated external defibrillators in public spaces for emergency use when someone has a heart attack.

There’s a long-held public stigma that suggests addiction is a moral failing rather than a chronic yet treatable health condition. Those who request naloxone or who have an opioid use disorder experience stigma and often aren’t comfortable disclosing their drug use to others, or seeking medical treatment. Removing naloxone’s prescription requirements by making it over the counter could decrease the stigma experienced by individuals since they no longer must request it from a health care provider or behind the pharmacy counter.

In addition, we encourage health care providers and members of the general public to use less stigmatizing language when discussing addiction.

Questionable accessibility

Often, medications switched from prescription to over the counter are not covered by insurance. It remains unclear if this will be the case with Narcan. If so, the costs will shift to the patient, highlighting the reason continued support of programs that offer naloxone free of charge remains important.

What’s more, over-the-counter access could paradoxically cause a decrease in the drug’s availability. A rise in purchases could make it harder to buy naloxone if manufacturer supply does not keep up with increased consumer demand. The U.S. experienced such shortages of over-the-counter drugs in late 2022 during the nationwide surges in flu, respiratory syncytial virus and COVID-19.

Federal and state governments could lessen these potential barriers by subsidizing the cost of over-the-counter naloxone and working with drug manufacturers to provide production incentives to meet public demand.

The effects of nationwide access to over-the-counter naloxone on opioid-related deaths remain to be seen, but making this medication more widely available is an important next step in our nation’s response to the opioid crisis.![]()

Lucas Berenbrok, University of Pittsburgh; Janice L. Pringle, University of Pittsburgh, and Joni Carroll, University of Pittsburgh

Lucas Berenbrok, Associate Professor of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, University of Pittsburgh; Janice L. Pringle, Professor of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, University of Pittsburgh, and Joni Carroll, Assistant Professor of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.