One morning in January, I found myself 30 feet (9 meters) up a tall metal pole, carrying 66 pounds (35 kilograms) of aluminum antennas and thick weatherproofed cabling. From this vantage point, I could clearly see the entire Punta Banda Estuary in northwestern Mexico. As I looked through my binoculars, I observed the estuary’s sandy bar and extensive mudflats packed with thousands of migratory shorebirds frenetically pecking the mud for food.

In winter, more than 1 million shorebirds that breed in the Arctic will visit and move throughout the coastline of northwest Mexico. It’s possible they are tracking rare superabundant seasonal resources like fish spawning events. Or maybe they are scouting for sites with better habitat to spend their nonbreeding season. The truth is, researchers don’t actually know. It has been incredibly hard to elucidate how birds use the region and what drives their movements in this vast network of coastal wetlands spanning 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) of coastline.

Julián García Walther, CC BY-ND

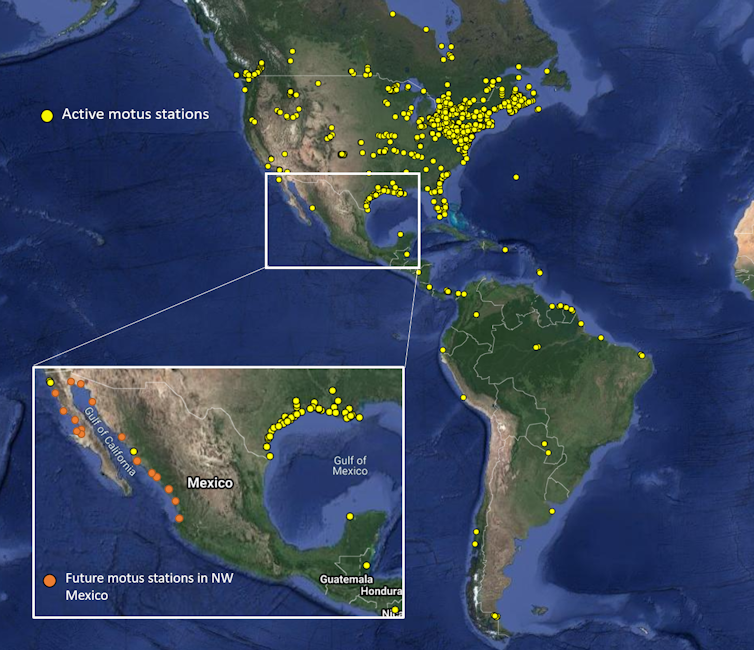

Tracking birds has always been a challenge. To make it easier, scientists have built a massive network of radio antenna devices called Motus stations across the U.S. and Canada that can automatically track the movements of tagged birds. However, Motus stations – Motus means movement in Latin – are still missing in much of Latin America. This has resulted in large gaps in biologists’ understanding of where migratory shorebirds go during their nonbreeding season.

A biology doctoral student studying bird migration, I am collaborating with the nonprofit Pronatura Noroeste. We have one goal: to expand the Motus network in northwest Mexico and unravel the mystery of where shorebirds are going during the winter.

How to track a bird

Much of my work is focused on red knots – stubby sandpipers that feed on muddy flats that are uncovered during low tide in many estuaries.

In the past, to learn how red knots move among wetlands meant walking through knee-deep mud with a scope, trying to find birds with color-coded flags on their legs. I would then have to get close enough to read the writing on the flags to determine who had attached the flag and where in the continent the bird had been seen before. This is not easy work. It requires large numbers of flagged birds and many skilled ecologists trying to find them, so you get very limited data in return for a lot of time and effort.

Motus stations make this job much easier, and with a Motus network in Mexico, ecologists like me will get much more data on the movements of these animals. The project involves two parts: attaching tiny radio transmitters to birds and building a network of stations to track them.

Motus stations work similarly to a cellphone tower. Researchers attach tiny transmitters weighing just 0.45 grams to animals and these transmitters emit a radio pulse every five seconds. Each station has multiple antennas pointing toward a site used by birds – like the mudflats at Punta Banda – and is always listening for these radio signals.

Motus stations can pick up signals from tagged birds in a 12-mile (20-kilometer) radius, 24/7. A small computer built into the Motus station can then record and send information to researchers about when animals arrive to the site, how long they stay and in which direction they are headed when they leave.

Julián García Walther, CC BY-ND

Building a network

The station at Punta Banda is the first and, so far, the only tower my team and I have erected. But the ultimate goal of our project is to deploy two dozen Motus stations in 15 coastal wetlands spanning the whole northwest coast of Mexico. When we are done, we will use these stations to track the movements of birds among these sites, as well as the more than 1,000 other sites with active stations across the world.

The Punta Banda Estuary is one of the key stopovers for red knots. To maximize our chances of detecting birds, we chose to build the station on top of an old 30-foot metal pole overlooking the whole estuary. After getting approval from the pole owner, my colleagues and I assembled the station components. Then I climbed the pole, hoisting multiple antennas with me, and pointed them in all directions over the estuary.

By the time red knots start arriving in the fall, after breeding in the Arctic, our team hopes to have built many more stations like this one across northwest Mexico, ready to detect passing birds.

Tagging birds

The stations alone can’t detect these animals. The final step, which will happen in the coming months, is to catch birds and tag them. To do this, our team will set up a soft, spring-loaded net called a whoosh net in sandy areas where the red knots rest above the high-tide line. When birds walk past the net, the crew leader will release the trigger, safely trapping the birds with the net.

Once we’ve successfully caught a bird, we will attach a transmitter to its back. Transmitters are solar-powered and very light – less than 1% of the bird’s weight – and they can thus provide many years of data without harming the birds. Because younger birds may move differently than adults across the region, our team hopes to tag 130 red knots of different ages at other estuaries in northwest Mexico. The larger Motus project has already tagged more than 25,000 animals, so any other birds that come to northwest Mexico will also get picked up by our stations.

Filling important gaps in knowledge

Migratory shorebirds are among the most threatened bird groups. Their populations have plummeted by 37% since 1970 owing to habitat loss, human disturbance and climate change. Without robust information on how birds use important sites like the ones we are working on in Mexico, it is hard to focus conservation actions when and where they are most needed. As our network of stations grows, the data they collect will help fill critical knowledge gaps.

For researchers like me, this data will allow us to understand how the movement of shorebirds might be disrupted as global threats such as sea level rise continue to affect the coastal wetlands they depend on. In turn, conservationists will be able to implement better and more effective on-the-ground actions to conserve species like red knots.![]()

Julián García Walther, University of South Carolina

Julián García Walther, PhD Student in Ornithology, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.