In times of mortal strife, humans crave information more than ever, and it’s journalists’ responsibility to deliver it.

But what if that information is inaccurate, or could even kill people?

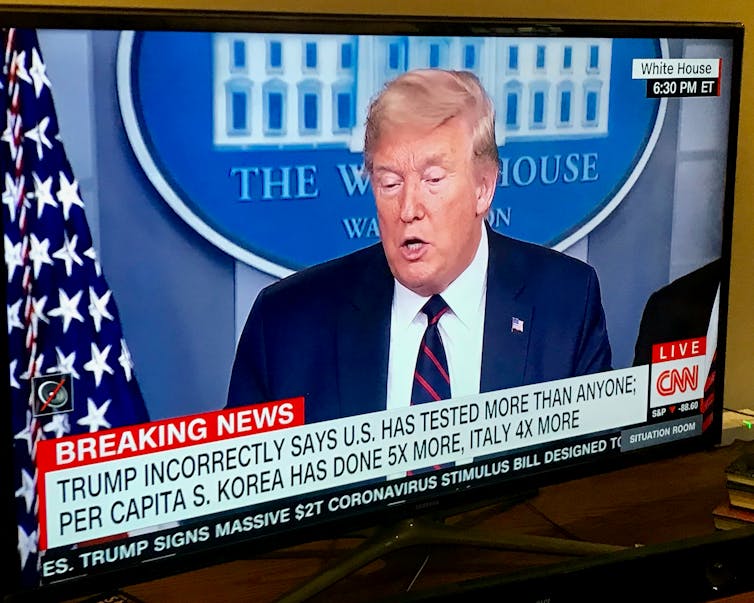

That’s the quandary journalists have found themselves in as they decide whether to cover President Donald J. Trump’s press briefings live.

Some television networks have started cutting away from the briefings, saying the events are no more than campaign rallies, and that the president is spreading falsehoods that endanger the public.

“If Trump is going to keep lying like he has been every day on stuff this important, we should, all of us, stop broadcasting it,” MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow tweeted. “Honestly, it’s going to cost lives.”

News decisions and ethical dilemmas aren’t simple, but withholding information from the public is inconsistent with journalistic norms, and while well-meaning, could actually cause more harm than good in the long run. Keeping the president’s statements from the public prevents the public from being able to evaluate his performance, for example.

Truth and falsehood can fight it out

The Society of Professional Journalists’ code of ethics, updated in 2014 during my term as president, states that the press must “seek truth and report it,” while also minimizing harm.

When the president of the United States speaks, it matters – it is newsworthy, it’s history in the making. Relaying that event to the public as it plays out is critical for citizens, who can see and hear for themselves what their leader is saying, and evaluate the facts for themselves so that they may adequately self-govern.

That’s true even if leaders lie. Actually, it’s even more important when leaders lie.

Think of libertarian philosopher John Milton’s plea for the free flow of information and end of censorship in 1600s England. Put it all out there and let people sort the lies from the truth, Milton urged: “Let her and Falsehood grapple.”

If a president spreads lies and disinformation, or minimizes health risks, then the electorate needs to know that to make informed decisions at the polls, perhaps to vote the person out to prevent future missteps.

Likewise, there’s a chance the president could be correct in his representation of at least some of the facts.

It’s not up to journalists to decide, but simply report what is said while providing additional context and facts that may or may not support what the president said.

Maddow is correct that journalists should not simply parrot information spoon fed by those in power to readers and viewers who might struggle to make sense of it in a vacuum. That is why it’s imperative journalists continuously challenge false and misleading statements, and trust the public to figure it out.

Craving information

Those who would urge the media’s censorship of the president’s speeches may feel they are protecting citizens from being duped, because they believe the average person can’t distinguish fact from fiction. Communication scholars call this “third-person effect,” where we feel ourselves savvy enough to identify lies, but think other more vulnerable, gullible and impressionable minds cannot.

It is understandable why journalists would try to protect the public from lies. That’s the “minimizing harm” part in the SPJ code of ethics, which is critical in these times, when inaccurate information can put a person’s health at risk – or cause them to make a fatal decision.

So how do journalists report the day’s events while minimizing harm and tamping down the spread of disinformation? Perhaps this can be accomplished through techniques already in use during this unorthodox presidential period:

- Report the press briefings live for all to see, while providing live commentary and fact-checking, as PolitiFact and others have done for live presidential debates.

- Fact-check the president after his talks, through contextual stories that provide the public accurate information, in the media and through websites such as FactCheck.org.

- Call intentional mistruths what they are: Lies. With this administration, journalists have become more willing to call intentional falsehoods “lies,” and that needs to continue, if not even more bluntly.

- Develop a deep list of independent experts that can be on hand to counter misinformation as it is communicated.

- Report transparently and openly, clearly identifying sources, providing supplemental documents online, and acknowledging limitations of information.

The coronavirus pandemic is a critical time for the nation’s health and its democracy. Now, more than ever, we need information. As humans, we crave knowing what is going on around us, a basic “awareness instinct,” as termed by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel in their foundational book, “The Elements of Journalism.”

‘People aren’t dummies’

Sometimes people don’t even realize they need information until after they have lost it.

In his autobiography, the late Sen. John McCain wrote that upon his release after five years as a Vietnamese prisoner of war, the first thing he did when he got to a Philippines military base was order a steak dinner and stack of newspapers.

“I wanted to know what was going on in the world, and I grasped anything I could find that might offer a little enlightenment,” McCain wrote. “The thing I missed most was information – free, uncensored, undistorted, abundant information.”

People aren’t dummies. They can decipher good information from bad, as long as they have all the facts at their disposal.

And journalists are the ones best positioned to deliver it.

David Cuillier, University of Arizona

David Cuillier, Associate Professor, School of Journalism, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.