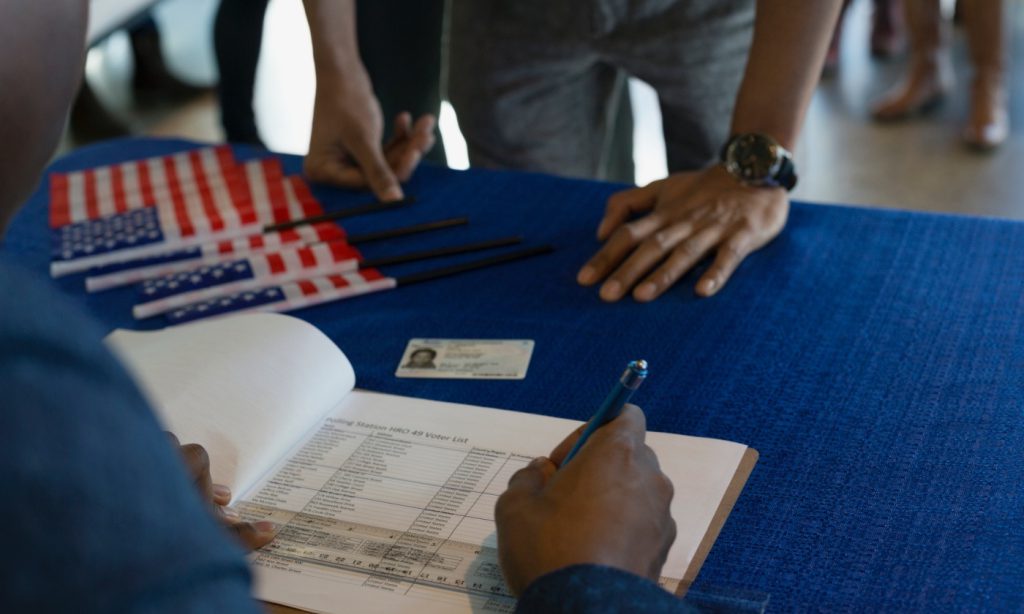

And several other reasons that the midterm elections are testing how far some states can go in disenfranchising certain voters.

What if we had an election and everyone came?

That’s not a hypothetical question, because we’re right now in the middle of the midterm election season where one of the two political parties is trying to make sure fewer people are going to vote.

Midterms are said to be a referendum on the incumbent president, but probably nothing is more at stake than elections for state legislatures. Whoever controls the state houses in 2018 will be in charge of redistricting after the 2020 Census—and that happens before the 2020 presidential election, when President Trump actually will be on the ballot.

The fact that, according to Cook Political Report, as of Oct. 12, 327 out of 435 House of Representatives seats are considered locks by one of the two big parties points to how antidemocratic the whole system has become.

Turnout in midterms is historically low, but there are signs that this year might be different. Pew Research saw a surge of voting in the primaries by more than 50 percent over the 2014 midterms. Call it the Trump Effect, or call it something else, these midterms are shaping up to be one of those turning points that determine the direction of the nation for decades to come.

It may be because the right to vote is essentially on the ballot in this election. The conservative writer David Frum in January wrote in The Atlantic about the dilemma we’re now facing in the United States: “If conservatives become convinced that they cannot win democratically, they will not abandon conservatism. They will reject democracy.”

We’re now seeing that situation play out in the midterms. In the five years since the Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, gutted the key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, many states in the South and the Midwest controlled by Republicans have enacted voter registration laws that disenfranchise minority voters.

Consider Georgia, where Democrat Stacey Abrams is running to be the first Black female governor in the nation’s history. Her opponent, Republican Secretary of State Brian Kemp, has been aggressively purging voters from the registration lists, aided by a draconian “100 percent match” law that allows tiny changes in spelling, such as a typo or a dropped hyphen in a last name, as grounds for disenfranchisement.

Last week it was revealed that, in addition to purging a half-million voters from the rolls in the past five years, Kemp was refusing to process 53,000 voter registrations, 70 percent of which are for Black or Latino residents, and requiring them to cast provisional ballots. As a candidate, Kemp has refused to recuse himself from his role as the overseer of Georgia’s elections system .

Abrams meanwhile has called on Kemp to resign, and a number of civil rights groups have filed suit against him. Georgia’s voter registration deadline is Tuesday, Oct. 16.

Georgia is not an outlier. Across the country, there are measures both subtle and obvious that target the voting rights of the most marginalized communities.

The Supreme Court last week allowed North Dakota to implement a voter ID law that requires an identification with a street address, something that many Native Americans living on reservations or in rural areas don’t have. And while North Carolina’s previous voter ID law was tossed out for being unconstitutional for its targeting of Black voters, the state is heavily gerrymandered in favor of Republicans. It has closed early voting polling places in almost half of its counties, eliminated early voting on the last Saturday before Election Day, and is requiring voters to carry photo ID to the polls.

It’s easy to believe that, short of intervention by the Supreme Court (now with a solid far-right-wing majority in place, thanks to Brett Kavanaugh), the right to vote will remain a contested battleground.

But let’s assume for the moment that well-intentioned people will take control of state houses and governor’s offices. What would a fair voting system look like?

There have been many experiments in the states, the original “laboratories of democracy.” Washington, Oregon, and Colorado have voting by mail for all elections: no lines at the polls, no easily hackable voting machines, no party operatives challenging your right to vote if they don’t like the way you look. These states don’t have a single election day, they have an election window. There’s evidence that turnout is higher, too.

Arizona’s Proposition 106, passed in 2000, took the job of drawing districts out of the hands of the legislature and gave it to an independent redistricting commission, something several other states also do. That’s made races more competitive and also increased participation. More states are looking to follow that example, such as Utah, where Proposition 4 is on the ballot this November, asking voters to approve creating a commission to submit maps to the legislature for approval.

Maine approved ranked-choice voting this year. The method has been touted as more representative of voters’ intents. It also prevents a spoiler effect in races with more than two candidates. Presidential elections likely would have gone another way both in 2000 and 2016 had such as system been in place nationally—the tally would have tracked more closely to the popular vote, even with the Electoral College still in place.

Automatic Voter Registration has long been the Holy Grail of a robust democracy: get a driver’s license or state ID, get registered to vote. Thirteen states and Washington, D.C., use it. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, 20 states have introduced or carried over bills that either implement or strengthen it.

And what about eliminating voter registration altogether?

Why not go further? What if voting were compulsory, as it is in Australia and some Latin American countries? Obviously it increases turnout, but it also makes it difficult for anyone seeking to disenfranchise voters for any reason. Races become about candidates and issues, not about thwarting entire classes of voters.

And what about eliminating voter registration altogether?

The registration system has its roots in racially based disenfranchisement in the 19th century. In France and Sweden, if you’re a citizen, you can vote, period. Even North Dakota does it. It doesn’t mean you don’t need other protections (see North Dakota’s Voter ID law above) but it does mean that there are fewer barriers.

There’s an even more radical possibility: proportional representation. If one political party wins 49.9 percent of the popular vote in congressional races, as the Republicans did in 2016, they would be entitled to 49.9 percent of the seats (as opposed to 55.2 percent they actually took).

Proportional representation is enshrined in the Constitution in how House seats are divided among the states—populous states such as California and Texas get more seats than Wyoming and Vermont. But how states elect people to fill those seats is far from proportional.

Gerrymandering of districts and a winner-take-all system skew the results in favor of whoever controls the state legislature. In North Carolina in 2016, Republicans earned 53.2 percent of the votes in congressional races, Democrats won 46.6 percent, while the rest went to third-party candidates. In a proportional system, that would give Republicans seven seats in the House of Representative and Democrats six. Instead, because of blatant partisan drawing of the districts, Republicans now hold 10 seats and the Democrats just three.

Despite state judges determining those district maps were unconstitutional, North Carolina will still head to the midterms with races weighted heavily in favor of Republican candidates because there wasn’t time to redraw the districts fairly.

It might take a constitutional amendment to enact proportional representation over the entire country, so it’s a long shot. But it can eliminate the problems of gerrymandering and with spoiler races. And if not everyone can get everything they want, most people will get something, and third-party candidates would have a more realistic shot.

None of these ideas are outlandish. Each of them has been implemented somewhere. All that is required is that our political leaders be well-intentioned.

Perhaps that’s a stretch of the imagination in the current political mood. But it happened once before in 1789, when a group of people came together to create a system of government that embraced a robust democracy. We’re a country still capable of thinking that big.