On July 20, 2022, President Joe Biden traveled to a former coal-burning power plant in Massachusetts that is being converted into a manufacturing site for offshore wind power equipment. Biden announced millions of dollars in funding for climate change measures, including upgrading infrastructure, weatherizing buildings and installing cooling in homes. He also touted job growth from clean energy production and pledged to use all of his executive power to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

But Biden did not declare a national climate emergency – a step that some Democratic officials and activists have urged after Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin seemingly blocked legislative action and the Supreme Court limited the Environmental Protection Agency’s power to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

According to White House officials, an emergency declaration remains an option. As a legal scholar who has analyzed the limits of presidential power, I believe that declaring climate change to be a national emergency could have benefits, but also poses risks.

Taking that route sets an important precedent. If presidents increasingly make free use of emergency powers to achieve policy goals, this approach could become the new normal – with a serious potential for abuse of power and ill-considered decisions.

Yesterday, the border; today, the climate

President Donald Trump declared a national emergency on border security on Feb. 15, 2019, after Congress refused to fund most of his US$5.7 billion request for border wall construction. As Trump’s intent became clear, Republican Sen. Marco Rubio warned that “tomorrow the national security emergency might be, you know, climate change.”

Rubio was right to take this possibility seriously. In my view, declaring a climate emergency would probably be legal and would unlock provisions in many laws that authorize the president or subordinates to take specific actions under a national emergency declaration.

Like Trump, Biden might use the power to divert military construction funds to other projects, such as renewable energy projects for military bases. Biden could also use trade measures – for example, restricting imports from countries with high carbon emissions, or perhaps imposing a carbon fee on goods from those countries to level the playing field.

Another potential action would be ordering businesses to produce certain goods. The Trump administration used the Defense Production Act, a law dating from the 1950s, to expand production of medical supplies for treating coronavirus patients. Biden has already used the law to accelerate domestic production of solar panel parts, insulation and other clean energy technologies.

After declaring an emergency, Biden could provide loan guarantees to critical industries in order to help finance goals such as expanding renewable energy production. Oil and gas leases on federal lands and in federal waters contain clauses that allow the Interior Department to suspend them during national emergencies, though that seems unlikely in the immediate future given current gas prices.

Declaring a national emergency would also enable the president to limit oil exports to other countries – although this also appears unlikely given the war in Ukraine, which has increased European reliance on U.S. oil. Biden also could limit U.S. financing for foreign coal projects.

Would it be legal?

Emergency powers are only available assuming climate change qualifies as an emergency. The law empowering presidents to declare national emergencies doesn’t define the term.

Among recent precedents, President Barack Obama declared a cybersecurity emergency, and Trump declared that steel imports were an urgent threat to national security.

It’s not hard to make a case that climate change is an equally critical problem, especially with much of the world suffering through record-breaking heat waves and wildfires. There’s also clear support for the idea that climate change is a major national security threat.

To date, courts have never overturned a presidential emergency declaration, and a climate emergency would probably not be an exception. Legal challenges to Trump’s border security declaration failed.

However, the Supreme Court’s recent decision in West Virginia v. EPA adds a wild card to the legal analysis. The court ruled that certain actions are so important that they require extra clear authority from Congress. How the Court would apply this doctrine in the context of the National Emergencies Act remains unclear.

Frustration with gridlock

Emergency actions can sometimes shortcut bureaucratic procedures and reduce the potential for litigation, compared to the normal cumbersome regulatory process. That makes them faster and more decisive. They also place responsibility squarely on the president, which increases political accountability. There’s no question of who to blame if you don’t like the border wall – or emergency climate actions.

Unlike legislation, an emergency action does not have to move through Congress. And compared with most federal regulations, there is less requirement for transparency or public comment, and less room for judicial oversight.

That can speed things up, but it also makes major mistakes more likely. The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II is a vivid example.

In addition, once an emergency is declared, civil libertarians fear that a president could use emergency powers in laws that aren’t even related to that emergency. “Even if the crisis at hand is, say, a nationwide crop blight, the president may activate the law that allows the secretary of transportation to requisition any privately owned vessel at sea,” wrote Elizabeth Goiten, director of the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program.

Legislating is difficult and time-consuming. It requires the agreement of both houses of an increasingly polarized Congress. The filibuster rule requires 60 votes in the Senate for most legislation, and right now the Democrats don’t seem to be able to muster even the 50 votes they would need to take advantage of the “reconciliation” exception to this requirement.

But there are also real dangers to invoking emergency powers. Normalizing their use could make these expanded presidential powers hard to limit.

Congress can nullify emergency declarations by passing a resolution of disapproval, but this has proved ineffective in practice. For instance, despite bipartisan support, Congress failed to muster veto-proof margins for two resolutions overturning Trump’s border emergency, which the administration used to divert billions of dollars to wall construction.

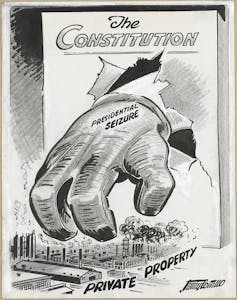

As Justice Robert Jackson wrote in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer – a famous 1952 Supreme Court decision in which the court held that President Harry Truman did not have the constitutional authority to nationalize the U.S. steel industry during the Korean War – emergency powers “afford a ready pretext for usurpation,” and the potential for using those powers “can tend to kindle emergencies” to justify their use.

Unlike some observers, I still see room for making real progress through the normal regulatory process. In my view, it’s not time yet for Biden to break the glass and pull the red emergency lever.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on March 9, 2020.![]()

Daniel Farber, University of California, Berkeley

Daniel Farber, Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.