Harriet Tubman was barely 5 feet tall and didn’t have a dime to her name.

What she did have was a deep faith and powerful passion for justice that was fueled by a network of Black and white abolitionists determined to end slavery in America.

“I had reasoned this out in my mind,” Tubman once told an interviewer. “There was one of two things I had a right to, liberty, or death. If I could not have one, I would have the other; for no man should take me alive.”

Though Tubman is most famous for her successes along the Underground Railroad, her activities as a Civil War spy are less well known.

As a biographer of Tubman, I think this is a shame. Her devotion to America and its promise of freedom endured despite suffering decades of enslavement and second class citizenship.

It is only in modern times that her life is receiving the renown it deserves, most notably her likeness appearing on a US$20 bill in 2030. The Harriet Tubman $20 bill will replace the current one featuring a portrait of U.S. President Andrew Jackson.

In another recognition, Tubman was accepted in June 2021 to the United States Army Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. She is one of 278 members, 17 of whom are women, honored for their special operations leadership and intelligence work.

Though traditional accolades escaped Tubman for most of her life, she did achieve an honor usually reserved for white officers on the Civil War battlefield.

After she led a successful raid of a Confederate outpost in South Carolina that saw 750 Black people rescued from slavery, a white commanding officer fetched a pitcher of water for Tubman as she remained seated at a table.

A different education

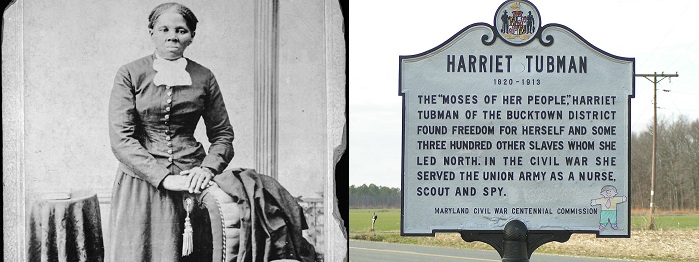

Believed to have been born in March 1822 in Dorchester County, Maryland, Tubman was named Araminta by her enslaved parents, Rit and Ben Ross.

“Minty” was the fifth of nine Ross children. She was frequently separated from her family by her white enslaver, Edward Brodess, who started leasing her to white neighbors when she was just 6 years old.

At their hands, she endured physical abuse, harsh labor, poor nutrition and intense loneliness.

As I learned during my research into Tubman’s life, her education did not happen in a traditional classroom, but instead was crafted from the dirt. She learned to read the natural world – forests and fields, rivers and marshes, the clouds and stars.

She learned to walk silently across fields and through the woods at night with no lights to guide her. She foraged for food and learned a botanist’s and chemist’s knowledge of edible and poisonous plants – and those most useful for ingredients in medical treatments.

She could not swim, and that forced her to learn the ways of rivers and streams – their depths, currents and traps.

She studied people, learned their habits, watched their movements – all without being noticed. Most important, she also figured out how to distinguish character. Her survival depended on her ability to remember every detail.

After a brain injury left her with recurring seizures, she was still able to work at jobs often reserved for men. She toiled on the shipping docks and learned the secret communication and transportation networks of Black mariners.

Known as Black Jacks, these men traveled throughout the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic seaboard. With them, she studied the night sky and the placement and movement of the constellations.

She used all those skills to navigate on the water and land.

“… and I prayed to God,” she told one friend, “to make me strong and able to fight, and that’s what I’ve always prayed for ever since.”

Tubman was clear on her mission. “I should fight for my liberty,” she told an admirer, “as long as my strength lasted.”

The Moses of the Underground Railroad

In the fall of 1849, when she was about to be sold away from her family and free husband John Tubman, she fled Maryland to freedom in Philadelphia.

Between 1850 and 1860, she returned to the Eastern Shore of Maryland about 13 times and successfully rescued nearly 70 friends and family members, all of whom were enslaved. It was an extraordinary feat given the perils of the 1850 Slave Fugitive Act, which enabled anyone to capture and return any Black man or woman, regardless of legal status, to slavery.

Those leadership qualities and survival skills earned her the nickname “Moses” because of her work on the Underground Railroad, the interracial network of abolitionists who enabled Black people to escape from slavery in the South to freedom in the North and Canada.

As a result, she attracted influential abolitionists and politicians who were struck by her courage and resolve – men like William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown and Frederick Douglass. Susan B. Anthony, one of the world’s leading activists for women’s equal rights, also knew of Tubman, as did abolitionist Lucretia Mott and women’s rights activist Amy Post.

“I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years,” Tubman once said. “and I can say what most conductors can’t say; I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

Battlefield soldier

When the Civil War started in the spring of 1861, Tubman put aside her fight against slavery to conduct combat as a soldier and spy for the United States Army. She offered her services to a powerful politician.

Known for his campaign to form the all-Black 54th and 55th regiments, Massachusetts Gov. John Andrew admired Tubman and thought she would be a great intelligence asset for the Union forces.

He arranged for her to go to Beaufort, South Carolina, to work with Army officers in charge of the recently captured Hilton Head District.

There, she provided nursing care to soldiers and hundreds of newly liberated people who crowded Union camps. Tubman’s skill curing soldiers stricken by a variety of diseases became legendary.

But it was her military service of spying and scouting behind Confederate lines that earned her the highest praise.

She recruited eight men and together they skillfully infiltrated enemy territory. Tubman made contact with local enslaved people who secretly shared their knowledge of Confederate movements and plans.

Wary of white Union soldiers, many local African Americans trusted and respected Tubman.

According to George Garrison, a second lieutenant with the 55th Massachusetts Regiment, Tubman secured “more intelligence from them than anybody else.”

In early June 1863, she became the first woman in U.S. history to command an armed military raid when she guided Col. James Montgomery and his 2nd South Carolina Colored Volunteers Regiment along the Combahee River.

While there, they routed Confederate outposts, destroyed stores of cotton, food and weapons – and liberated over 750 enslaved people.

The Union victory was widely celebrated. Newspapers from Boston to Wisconsin reported on the river assault by Montgomery and his Black regiment, noting Tubman’s important role as the “Black she Moses … who led the raid, and under whose inspiration it was originated and conducted.”

Ten days after the successful attack, radical abolitionist and soldier Francis Jackson Merriam witnessed Maj. Gen. David Hunter, commander of the Hilton Head district, “go and fetch a pitcher of water and stand waiting with it in his hand while a black woman drank, as if he had been one of his own servants.”

In that letter to Gov. Andrew, Merriam added, “that woman was Harriet Tubman.”

Lifelong struggle

Despite earning commendations as a valuable scout and soldier, Tubman still faced the racism and sexism of America after the Civil War.

When she sought payment for her service as a spy, the U.S. Congress denied her claim. It paid the eight Black male scouts, but not her.

Unlike the Union officers who knew her, the congressmen did not believe – they could not imagine – that she had served her country like the men under her command, because she was a woman.

Gen. Rufus Saxton wrote that he bore “witness to the value of her services… She was employed in the Hospitals and as a spy [and] made many a raid inside the enemy’s lines displaying remarkable courage, zeal and fidelity.”

Thirty years later, in 1899, Congress awarded her a pension for her service as a Civil War nurse, but not as a soldier spy.

When she died from pneumonia on March 10, 1913, she was believed to have been 91 years old and had been fighting for gender equality and the right to vote as a free Black woman for more than 50 years after her work during the Civil War.

Surrounded by friends and family, the deeply religious Tubman showed one last sign of leadership, telling them: “I go to prepare a place for you.”![]()

Kate Clifford Larson, Brandeis University

Kate Clifford Larson, Visiting Scholar Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.