Land in eastern Oklahoma that the United States promised to the Creek Nation in an 1833 treaty is still a reservation under tribal sovereignty, at least when it comes to criminal law, the Supreme Court ruled on July 9. Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the majority, “Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.”

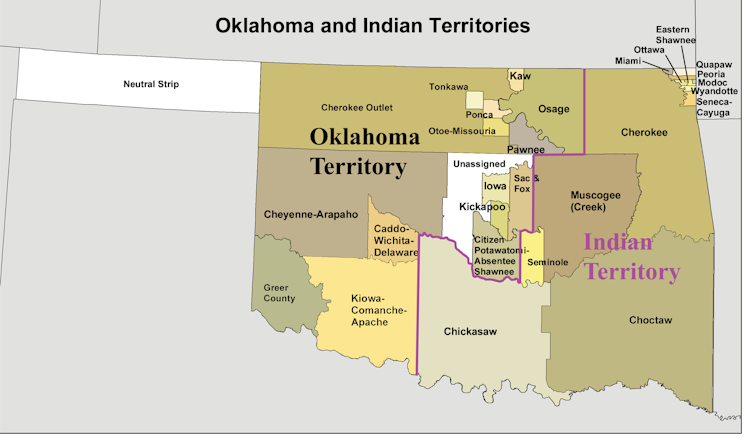

Kmusser, based on 1890s data/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

To most Americans, it may seem obvious that a government should live up to its word. But the United States has regularly reneged on the promises that it made to American Indian nations in the nearly 400 treaties that it negotiated with them between 1778 and 1871. Many people feared that the Supreme Court would turn a blind eye to another treaty breach in this case, McGirt v. Oklahoma.

For decades, the state of Oklahoma has prosecuted tribal citizens for committing crimes on lands in eastern Oklahoma that the United States granted to tribes in treaties. In 1997, Jimcy McGirt, a citizen of the Seminole Nation, was convicted in an Oklahoma state court of three sex crimes, including rape, that happened within the historic territory of the Creek Nation. He was sentenced to 500 years in state prison.

McGirt argued that the judgment was invalid because under an 1885 federal law, only federal courts – not state courts – have the authority to try American Indians accused of committing serious crimes on Indian reservations.

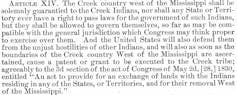

Treaty with the Creeks, Oklahoma State University Library

Treaty with the Creeks, Oklahoma State University Library

Who has jurisdiction?

In response to McGirt, Oklahoma had argued that even if the treaty granting land to the Creek Nation created a reservation, that treaty was no longer relevant. Oklahoma claimed that the lands, which included the places where McGirt’s alleged crimes happened, were no longer under tribal jurisdiction.

As the case made its way through state courts and then to the Supreme Court, Oklahoma claimed that even if the land was within the Creek reservation and therefore under Creek Nation jurisdiction, the state should be allowed to continue to prosecute tribal citizens on the land because it had done so for decades.

But the Supreme Court ruled that the terms of an 1833 treaty still apply, acknowledging that the Creek Nation had received the lands in eastern Oklahoma as partial compensation for surrendering and leaving their lands in what are now parts of Alabama, Georgia, Florida and South Carolina. The court affirmed that the Creek lands in Oklahoma land remain the tribe’s reservation.

Gorsuch wrote, in a 5-4 decision supported by justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, that the state’s prosecutions of American Indians for crimes on the tribe’s reservation violated federal law and the Creek Nation’s treaty rights.

“Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law,” he wrote. “To hold otherwise would be to elevate the most brazen and longstanding injustices over the law, both rewarding wrong and failing those in the right.”

For Oklahoma, the ruling means the state cannot continue to prosecute tribal citizens on tribal lands – which includes about half of Oklahoma’s territory because the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole nations have similar treaties with the United States granting them land in Oklahoma, too.

What comes next?

The state had argued in court that the ruling would cause all sorts of problems with law enforcement and the economy in Oklahoma. But within hours of the ruling, state officials and leaders of the five American Indian nations had released a joint statement assuring the public that they are negotiating agreements that will fix any problems that might arise.

The statement declared that all the authorities “are committed to ensuring that Jimcy McGirt … and all other offenders face justice for the crimes for which they are accused.” Under the Supreme Court decision, McGirt faces retrial by a federal court.

Beyond Oklahoma, the decision’s effects will vary by tribe and state. States from Florida to Michigan have sought to curtail tribal sovereignty, and this decision clearly affirmed tribal sovereignty and treaty rights. It also emphasized the limited powers that states have over American Indian tribes under the U.S. Constitution. States may now think twice before ignoring treaty promises or challenging tribal jurisdiction.

They may decide it’s better to negotiate than to fight in court.![]()

Kirsten Carlson, Wayne State University

Kirsten Carlson, Associate Professor of Law and Adjunct Associate Professor of Political Science, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/