U.S. Representative Katie Hill was the latest victim of a form of sexual abuse that’s become increasingly common: revenge porn.

Intimate photos of her were leaked to the media and published, without her consent, for the world to see – a transgression Hill suspects her estranged husband was behind. The photos implicated Hill in a sexual relationship with a congressional staffer, an accusation that potentially put Hill in violation of House ethics rules.

Hill, a 32-year-old freshman representative, ended up resigning her seat on October 27.

Yet some of the ensuing coverage, instead of zeroing in on the leaked photographs, centered on blaming Hill for not being careful enough.

“The best way to avoid being a victim of revenge porn is to not take nude selfies and send them to people,” political commentator Alice Stewart announced on CNN.

In an article titled “A Word to the Young,” New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd implored millennials to do a better job protecting themselves and their reputations online.

“Don’t leave yourself vulnerable by giving people the ammunition – or the nudes – to strip you of your dreams,” she wrote. “OK, millennials?”

Even House Speaker Nancy Pelosi brought up Hill’s “error in judgement” and noted that what you share online “can come back to haunt you.”

As someone who studies the effects of sexual violence, I’ve heard this kind of victim-blaming far too often. To me, “Be careful of the photos you take of yourself” sounds eerily similar to “Don’t wear suggestive clothing.” Sexual violence happens because of sexual perpetrators. It has nothing to do with the clothing people wear or the photos they take of themselves.

Make no mistake: Revenge porn is a form of sexual violence, with the same motivations, power dynamics and potential for psychological harm at play.

It can happen to anyone

Revenge porn falls under the umbrella of what scholars call “technological forms of sexual violence.”

Other examples include “nonconsensual pornography,” which specifically refers to photos that are taken for a partner’s eyes, only to be eventually disseminated to others; “up-skirting,” which involves snapping sexually intrusive photos, often of someone’s genitals, without their knowledge; and “sextortion,” a form of sexual blackmail that Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos fell prey to in early 2019.

What happened to Hill isn’t an outgrowth of millennial culture. The nonconsensual sharing of intimate images and videos has been happening for decades. For example, the first issue of Playboy featured nude images of Marilyn Monroe that Hugh Hefner used without her permission. A sex tape filmed by Pamela Anderson and her then-husband Tommy Lee was famously stolen and leaked in 1995.

But the growing role of digital technology in our everyday lives – and the ever-expanding scope of everyone’s digital footprint – has made more people vulnerable to this sort of abuse and exploitation.

One study from 2017 found that 1 in 12 participants reported that they’d had nude images taken of them and posted publicly against their wishes. In Australia, that number is 1 in 10 – a rate that jumps to 1 in 2 for those who are indigenous or report having a disability.

An Australian survey also found that 1 in 3 members of the LGBT community, like Rep. Hill and her alleged partner, report having intimate photos shared without their consent.

It can happen to anyone, at any age. Research from 2017 shows that almost 20% of reported victims are over the age of 50.

Control, retaliation and humiliation

Just as domestic violence was once misunderstood and tolerated, many people today fail to grasp how nude photographs can be wielded as weapons of abuse.

Yet the nonconsensual sharing of intimate images is a form of control, retaliation and humiliation, just like any other form of sexual violence.

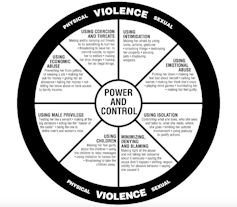

The Power and Control Wheel is a tool used by domestic violence experts to understand the ways in which domestic violence occurs in everyday interactions. Originally developed in 1993 by activists Ellen Pence and Michael Paymar, it demonstrates the abusive tactics beyond physical violence – such as withholding money, threatening to leave and isolating partners from friends and family – that are used to wield power and control.

Domestic Abuse Intervention Program

At this year’s Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues conference, psychologists Asia Eaton, Sofia Noori, Amy Bonomi, Dionne P. Stephens and Tameka L. Gillum explained how technological forms of sexual violence can be found in every category of the Power and Control Wheel. For example, one spoke of the wheel is economic abuse; another is coercion. It’s not difficult to see how intimate, private photographs can be wielded by an abusive partner to threaten someone’s job.

Abusive partners don’t even need nude photos to hurt their signficant others; photos or video footage can be altered via deepfake technology to create convincing and humiliating images.

The lasting psychological effects of having nude photographs of yourself shared online are just starting to emerge. The few studies that have been published show that victims deal with many of the same issues that survivors of rape and sexual harassment grapple with. One published in 2017 found evidence of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and suicidal thoughts among revenge porn victims. Other studies have shown how being targeted with revenge porn can lead to the development of trust and privacy issues that last a lifetime.

“Ever since those images first came out I barely left my bed,” Rep. Hill said during her final speech to the House of Representatives. “I went to the darkest places that a mind can go. I’ve hidden from the world.”

Those words ring all too familiar for victims who have endured sexual violence, both online and offline.

Instead of engaging in a victim blame narrative that accuses millennials of being shortsighted, let’s focus on the 1 in 20 Americans who perpetrate this form of abuse that violates privacy, causes psychological harm and ends careers.

Kristen Zaleski, Clinical Associate Professor of Social Work, University of Southern California

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/