When Colson Whitehead got the call, he’d just landed in North Carolina to do a reading at Duke. He was still on the plane when, he told the Guardian, “I called [my agent] back and she said, ‘Oprah.’ I said, ‘Shut the front door,’ because I didn’t want to curse. She said, ‘Oprah book club.’ I said, ‘Motherfucker.’”

Whitehead’s sixth novel, The Underground Railroad, getting chosen by Oprah was a door opening, or really more one blasting open—and Whitehead clearly knew it. Oprah’s stamp of approval on your book can make your career, massively boost your book sales, and get your book into the mainstream like really nothing else can, even a Nobel Prize. I mean, look at Toni Morrison. While I want to be clear that she is a literary genius whose impact was immense long before she got popular attention, consider that when Morrison’s debut novel, The Bluest Eye, was first published in 1970, it sold just 2,000 copies, according to Quartz. After being featured as an Oprah’s Book Club pick in 2000, it sold 800,000 copies.

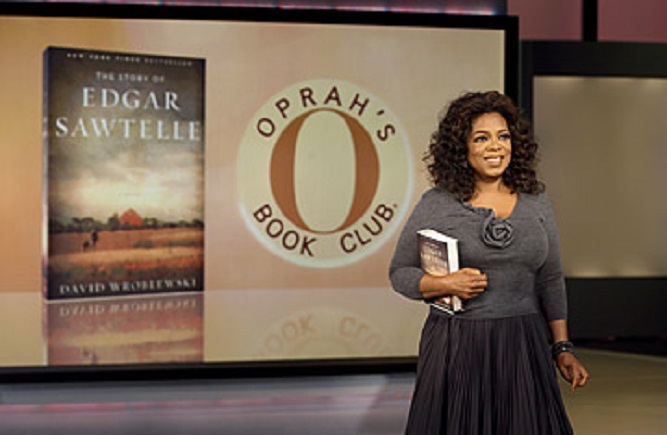

I was in middle school on September 17, 1996, when Oprah Winfrey stood in front of a studio audience in Chicago and announced she was starting the book club. But even though I didn’t consider myself—a basketball-loving tomboy growing up in San Francisco—part of her target demographic, I couldn’t escape her reach back then, and still now. This book club, through several evolutions and iterations, is the only part of the sprawling Oprah empire I genuinely care about. Her book club, for me—and I suspect a lot of other people, particularly in my age bracket—is the most culturally resonant part of her powerful legacy. I didn’t watch her talk show, am grumpily and somewhat naturally predisposed to be skeptical of her enthusiasm for All The Things, and despite my being a Leo and an only child, still can’t quite fathom putting my own face on the cover of a magazine every month for two decades.

“I’m putting these untold stories out there, because as a girl growing up, these stories were kind of hush hush, they were gossip. But to have our stories out there…it means a lot to me.”

But it would be treasonous to book nerds everywhere not to acknowledge the outsize impact Oprah’s had on publishing. And me. If one of the Oprah seals of approval catches my eye at the bookstore, I can’t help but stop. And with the club relaunching this month on Apple TV Plus, it’ll reach a whole new generation of people who I hope will get the same excitement finding the little orange O on a cover’s corner.

This is not just about the woman having good taste. This is about how Oprah, Patron Saint of Palatability, tells her millions of viewers not just that they should read, but what they should read. And, critically, those picks are often black writers who make race and America’s torrid racial history the center of their work. Of the 81 books Oprah has chosen since 1996, almost 30 are by authors of color. That’s not a bad track record—and the frequency of those picks has only increased in more recent years. She’s made black literature popular literature, from Morrison’s Paradise to Whitehead’s Underground Railroad to Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers. (Though this power can also boost people like Bill Cosby, who had three books on the list, and James Frey and his disgraced memoir, I’d argue it’s mostly been used for good.) She made what were largely taboo issues part of the pop culture conversation. She has the power to alter a reader’s perspective—on issues like reparations, slavery, and incarceration.

“It’s been so wonderful to see her use [her] platform to say, ‘I am invested in the stories that African Americans have to tell. And I believe that these stories are universally compelling,’” says Lisa Lucas, executive director of the National Book Foundation, which hosts the prestigious National Book Awards. “I think that has helped change the reception of stories that might’ve been marginalized otherwise.”

For writers like Nicole Dennis-Benn, praise from Oprah is also validation of their own work. “Of course [my] stories are told through Jamaican, working class women. They tackle universal themes like immigration, motherhood, belonging, acceptance, sexuality, colorism, classism, all those things,” she says of her two books, Patsy and Here Comes the Sun, which were both top picks in O, the Oprah Magazine. “I am so happy though that people are now seeing our stories and getting to kind of empathize with people who definitely look different from them or someone different from them.”

She adds, “I’m putting these untold stories out there, because as a girl growing up, these stories were kind of hush-hush, they were gossip. But to have our stories out there as working-class Jamaican women, people seeing us and hearing our voices, it means a lot to me.”

Back in ’96, when Oprah wanted to indulge with the world in her favorite pastime, it probably seemed like just that: an indulgence. “I wanna get the whole country reading again!” she beamed, as the camera panned to an audience of hopeful-looking women, most of them looking eager, blond, white.

But this in and of itself was an important image: A black woman born into poverty in Mississippi was just about singlehandedly dictating the tastes of a key, moneyed demographic of white women, who happened to influence white households and their buying practices, and also drive mass culture.