Leslie Lee calls herself an “artivist.” It’s a word combining art and activism, rooted in community and Latinx art from the late 1990s, but Lee says she was doing this work before it had a name.

“I have always been interested in metaphor and content that addressed various social issues,” she says. A 71-year-old grandmother, Lee has made art professionally as a sculptor and painter for more than 50 years, and she says she’s developed the “tenacity required for large-scale projects.”

In response to the October 2017 shooting deaths of concertgoers at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas, Lee established The Soul Box Project in Portland, Oregon, where she lives.

The project brings people together to make “Soul Boxes,” hand-folded paper boxes decorated with photos, written messages, or the name of a person killed by gunfire.

“Those who are personally deeply affected are often struggling to cope with trauma on a day-to-day basis,” Lee says. “Most of us are untouched by this gunfire epidemic, except as horrified onlookers.”

The lightweight boxes are connected one to another, side-by-side, and hand-tied to mesh panels, for easy transport and display. With each Soul Box representing a life, viewed collectively, they “[reveal] the staggering number of lives lost or torn apart,” she says.

In February 2019, 36,000 Soul Boxes were displayed at the Oregon capital of Salem—one for every person killed by gunfire in the U.S. in 2018, Lee says. The project approaches gun violence “from a grassroots, heart and gut level,” where people are ultimately moved to action.

In making an epidemic visible in a manner that reveals the massive scale of the problem, the Soul Box Project draws on one famous forebear, the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

-

A Soul Box Exhibit at the Multnomah Arts Center in Portland, Oregon, was held in April 2019. On display were 15,000 Soul Boxes, one for every person shot in the first three months of 2018. Photo by Soul Box volunteer.

The quilt helped raise awareness of HIV and AIDS, provided a societal push for more research and financial support, and quickly grew into the largest community artivism project in the world, Lee says. “When people felt the magnitude of the issue in their hearts, when research and education and treatments were activated, deaths from HIV plummeted.”

In 1995, 50,000 deaths from HIV/AIDS were reported in the U.S., according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. By 1998, thanks to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy and a major public health and education campaign, the number of deaths had fallen to about 20,000, and the annual death rate has gradually declined ever since, even as the number of people living with HIV has increased.

Efforts focused on gun control or other legislative solutions have often been stymied by the gun lobby. But Lee says the legal fix doesn’t address the whole picture, and her project takes no position on gun rights.

“The entire nation, on every side of the gun control issue, recoils with grief over the lost lives,” she says. “The question is not how we restrict or protect guns, so much as how we safely live with the arsenal that is already out there….”

“Folding a Soul Box is a nonconfrontational, nonpolitical way to take action. To express outrage or frustration. To honor a victim, [whereas] partisan politics is divisive. This project is meant to unite… to reach people on an emotional level,” Lee says.

-

Volunteers work on assembling display units in the Soul Box Project workshop at the Multnomah Arts Center in Portland. Photo by Soul Box volunteer.

Confronting emotions is at the heart of political art, and another project started by two Black activists uses some of the same techniques to highlight and address the stereotype of Black men as criminals, particularly the perception of a threat posed by Black men in hoodies, says Jason Sole, co-founder of Humanize My Hoodie.

The Humanize My Hoodie Movement takes a similar approach to inform, motivate, and engage community, to destigmatize clothing trends associated with Black and Indigenous people of color, says Sole, who himself was formerly incarcerated and is now a professor of criminal justice at Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

“Ultimately, our work was motivated by police killings,” Sole says. Confident that he could decrease racial bias in his students before they received their badges and guns, he started with a simple change in his appearance, teaching every class while wearing a hoodie. “I wanted the world to know that I’m a credible and reliable professor, whether in a suit or a hoodie,” he says.

Then, he dropped the hashtag #humanizemyhoodie, and it immediately took off on social media. Sole says that’s when fashion designer Andre’ Wright “jumped in the comments and asked that we broaden our scope and share it with the world.”

Wright, who owns the Born Leaders United fashion and leadership brand, put his business to work for the cause. The pair created hoodies with the message “Humanize My Hoodie” in bold type across the chest, and offered them for sale. It’s a message that empowers Black people and requires others to check their biases, Sole says.

The proceeds help maintain Humanize My Hoodie, which employs young people of color to manage the organization’s social media and run audio/video during events. Since 2017, the organization has given away hundreds of hoodies to youth of color. “We hope our brand is powerful enough to make an officer put their gun back in their holster and not kill us in the streets!” Sole says.

The movement drew the support of recording artist John Legend, who in August chose Humanize My Hoodie for his #CantJustPreach community leaders program and donated $10,000 to the campaign. Legend is actively promoting the organization alongside a small number of other causes.

-

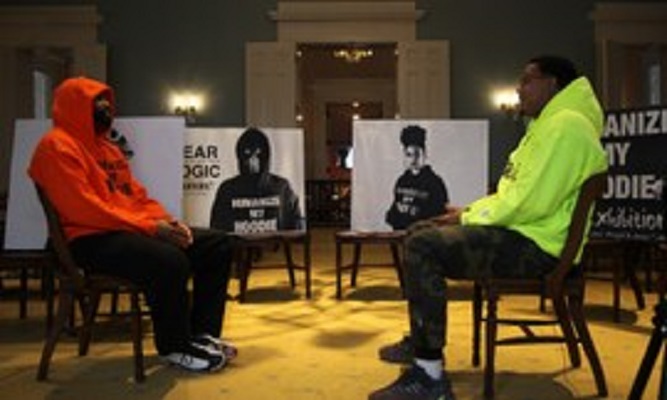

Jason Sole and Andre’ Wright (top) and others in the Council Chambers of the Old Capitol Museum in Iowa City, Iowa, during the Humanize My Hoodie art exhibition. Photo by Old Capitol Museum.

Schools and shopping malls both have been known to ban hoodies.

Sole says, “It doesn’t make sense that you can purchase hoodies in a clothing store at a mall but can’t step foot out of the store with that hoodie on.” But the message of the organization challenges those policies without saying a word.

It’s generating urgently needed conversation at a time when innocent Black men continue to face the threat of police violence rooted in stereotypes.

Sole relayed the experience of Minneapolis activist James Badue Jr., who stopped at a gas station, went in to make a purchase, then walked out. Heading to his car, he was met by a White man who apologized, relaying that when he saw Badue with his hood up, he thought he was about to rob the station, but when he later saw the message on the hoodie, he felt compelled to apologize. Sole says the men talked for 20 minutes.

When others see the words “Humanize My Hoodie,” Sole says, there’s an acknowledgement. “They either nod in support, look intently, ask what it means, or ask where they can purchase [a sweatshirt].”

-

Artwork from the Humanize My Hoodie traveling art exhibition at Old Capitol Museum. Photo by Old Capitol Museum.

Both the Soul Box Project and the Humanize My Hoodie Movement are focusing on shifting culture today and not waiting for incremental and underwhelming changes in law.

In just under two years, The Soul Box Project has held six exhibitions, brought in nearly 100 individual donors and won several grants, Lee says. Several public box-making sessions have taken place, and more than 63,000 boxes have been made.

Lee hopes to create an installation of 200,000 boxes on the National Mall in Washington by 2020.

Humanize My Hoodie also is launching a series of ally workshops to help White people identify their implicit biases. More than 150 people have taken part, so far. Sole says their goal is to reach 500 new allies by the end of 2019.

“On one hand,” he says, “we build with other amazing Black folks and on the other hand, we are holding systems accountable. We understand that slavery never ended. We seek liberation for our people and we do that by strengthening our relationships and standing up against injustices!”

By humanizing Black men with hoodies, Sole says, he hopes that the world can finally humanize Black men without them.