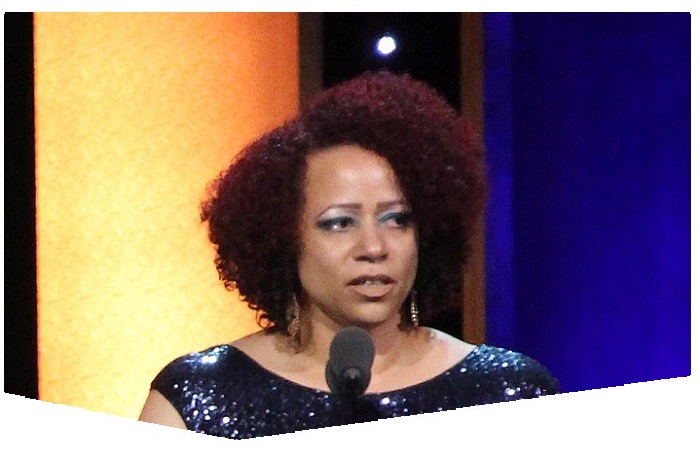

Her 1619 Project is at the center of a political battle over what students can learn about race in America.

Originally published by The 19th

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s board of trustees voted on Wednesday to grant tenure to Nikole Hannah-Jones after initially delaying the customary job protection for the incoming journalism professor, who is best known for her award-winning work reexamining how slavery shaped the United States’ founding.

The board’s vice chair, R. Gene Davis Jr., who was among those who voted to offer tenure to Hannah-Jones, said that UNC “is not a place to cancel people or ideas. Neither is it a place for judging people and calling them names, like woke or racist.”

“In this moment at our university, in our state, and in our nation, we need more debate, not less. We need more open inquiry, not less. We need more viewpoint diversity, not less. We need to listen to each other and not cancel each other, or call each other names. If not us, who?” Davis added in remarks after the 9-4 vote.

Davis alluded to the controversy that has surrounded the delay in granting Hannah-Jones tenure by saying “members of the board have endured false claims and been called the most unpleasant of names over the past few weeks.”

Hannah-Jones’ next steps were not immediately clear. Attorneys representing the MacArthur Foundation “genius” grantee and Pulitzer Prize winner said last week that she would not join UNC’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media as its Knight Chair in Race and Investigative Journalism unless it was with tenure, as professorships funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation traditionally are.

Hannah-Jones’ lawyers said UNC’s initial offer of a five-year contract, not tenure, reflected “race and sex discrimination and retaliation” as well as “viewpoint discrimination” in violation of state and federal laws. The latter was a reference to Hannah-Jones’ work on the 1619 Project, a ground-breaking series of essays, poems, graphics and visual art pieces she led at The New York Times Magazine that examined the arrival of the first enslaved Africans to the United States more than 400 years ago.

The UNC board’s deferment of Hannah-Jones’ tenure came over the objections of the faculty committee and amid concerns from a university mega-donor for whom the journalism school is named, the newspaper magnate Walter Hussman, who has subsequently said publicly that he was troubled by parts of the 1619 Project. Hussman suggested parts of history were embellished to bolster the project’s narrative.

The fallout from the tussle over Hannah-Jones’ tenure demonstrates how university boards increasingly receptive to political influence can make it more difficult for colleges to recruit and retain top-tier faculty if they are concerned their scholarship or research, or even their diverse backgrounds, might lead to political backlash. It also illustrates how classrooms, whether at state colleges or in public elementary schools, have become the latest high-profile battlefronts in a partisan war over who gets to have a voice in reexamining and retelling how race and slavery shaped our country’s history. The 1619 Project is at the center of the maelstrom.

Just one year after crowds took to the streets in cities across the country to protest race-related police shootings in a moment that many thought was a racial reckoning or turning point for White people, support for the Black Lives Matter movement has plummeted. At least 26 state legislatures have moved to restrict the teaching of what academics call critical race theory, and legislators in at least 48 states have proposed restrictive voting measures that experts believe would disproportionately impact voters of color. (Some, like in California, have little chance of passing Democratic-controlled legislatures.)

Hannah-Jones told MSNBC’s Joy Reid earlier this month that moves to limit teaching structural racism in classrooms and to restrict who can easily vote are a “reaction” to the racial awakening that some White Americans experienced last summer.

The 1619 Project has become the bogeyman because it “unsettles the narrative” of our country’s founding that has long been seen and taught from a White perspective, Hannah-Jones said, and “in unsettling that narrative, people are afraid it unsettles power.”

“It is really a need to hold onto and maintain that power and divide that social movement towards justice by making White Americans, at least a segment of them who will be susceptible to this message, believe that ‘actually no, you’re under attack, they’re trying to take your history, they’ve gone too far,’ and that’s why wedding this together is working so successfully,” she said.

The 1619 Project was published in August 2019, but it wasn’t until more than a year later that then-President Donald Trump invoked its impact when he signed an executive order establishing the 1776 Commission — named for the year the Declaration of Independence was signed — which he said would counter “recent attacks on our founding” that were “one-sided and divisive.” (President Joe Biden has since dismantled the commission).

“By viewing every issue through the lens of race, they want to impose a new segregation,” Trump said at the White House.

“Critical race theory, the 1619 Project and the crusade against American history is toxic propaganda, ideological poison, that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together,” he said.

Critical race theory is not new. It is an educational framework developed 40 years ago by legal scholars. Its central tenet is that racism is not only a belief held by some individuals but also embedded in societal institutions, and that individuals can, via the choices they make, support racist systems. One example would be “redlining,” a Depression-era federal housing program that segregated residents by race. The practice was ended in the 1960s but its impacts persist today. They were discussed during the 2020 Democratic presidential primary when Elizabeth Warren incorporated a housing bill she had introduced in the Senate into her primary platform.

The 1619 Project, which was accompanied by a related suggested curriculum that explores the legacies of slavery, thrust critical race theory to the forefront of arguments that have for years played out between liberals and conservatives over what subjects should be taught in schools.

Some historians criticized portions of the 1619 Project, saying they did not “question the significance of slavery in the American past” but thought the project offered a “historically-limited view of slavery” given it was not confined to the United States. Debate intensified when the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting began releasing the 1619 Project’s lesson plans.

Even as increasing numbers of Americans — 76 percent of adults, including 83 percent of women and 68 percent of men — agreed that racism and discrimination were a “big problem,” Trump’s Education Department, as part of a broader federal crackdown, began investigating whether its employees were discussing “anti-American” ideas and to identify any trainings or “propaganda” that discussed critical race theory or White privilege.

In the year since, bills have been signed into law in at least six states — Idaho, Iowa, Oklahoma, New Hampshire, Tennessee and Texas — that restrict the teaching of critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism in their lessons, according to Education Week.

In Idaho, Republican Gov. Brad Little signed such a law in April. Separately, there is an education “indoctrination” task force led by Lt. Gov. Janice McGeachin, who recently met with Trump and who is running for governor. Idaho high school students, who protested the law at the statehouse, recently told Education Week they are worried the task force will further prevent them from learning the fullest version of U.S. history.

The Utah State Board of Education approved a rule earlier this month that limits how teachers can teach racism or sexism. Florida’s board recently prohibited educators from teaching critical race theory or the 1619 Project. Montana Attorney General Austin Knudson last month issued a binding opinion that bars teachers from asking students to “reflect, deconstruct or confront” their racial privilege.

Arizona Republicans proposed a law that would fine teachers $5,000 for failing to present “all perspectives of a controversial issue,” but it did not pass. A conservative group in Nevada proposed outfitting teachers with body cameras to review whether they were teaching critical race theory.

Many of the laws, both proposed and passed, are vague and broadly written, raising free speech concerns that will likely lead to legal challenges. They nevertheless indicate the country has entered a “very dangerous period,” Hannah-Jones told MSNBC.

“When you read the language of them, they appear very silly, but when you think about what this is actually trying to do, we know that it is narrative that allows us to enact really dangerous policies, it is narrative that allows citizens to kind of accept these erosions of civil rights,” she said, adding: “It is not incidental that the same states that are introducing these anti-critical race theory, anti-1619 laws, are also introducing voter suppression laws.

Texas Democrats staged a walk-out in May to deny their Republican counterparts the quorum they needed to vote on a restrictive voting law. In May, GOP Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, signed a law to purge infrequent voters from the state’s popular Permanent Early Voting List.

On the federal level, a Democratic bill to expand voting rights has stalled in Congress. Critical race theory held up Kiran Ahuja’s confirmation to lead the Office of Management and Budget. Republican Sen. Tom Cotton from Arkansas earlier this year introduced a bill that would prohibit military institutions from teaching structural racism, saying it was “anti-American.” Republican lawmakers last week questioned military leaders about whether military schools such as West Point were teaching critical race theory, citing specific courses and a seminar titled “White rage.”

“I want to understand White rage and I am White,” said Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the joint chiefs of staff.

“What is it that caused thousands of people to assault this building and try to overturn the constitution of the United States of America? What caused that? I want to find that out,” he added, referencing the January insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

Milley served under both Trump and Biden.

For now, critical race theory and the 1619 project are dominating headlines, but not the minds of the average American voter — at least by name. A recent Morning Consult poll showed that 35 percent of voters have not heard of it, and another 17 percent have heard of it but have no opinion. Women were more likely than men to say they were unaware of the educational framework and, if they did, reported having less strong feelings about it either way.

A Bellwether Research poll published on Wednesday indicates that the terms “critical race theory” and “1619 Project” are not yet widely known among women voters and offered a mixed view of how women feel about their underlying concepts.

The Bellwether poll showed that 34 percent of women voters had not heard of critical race theory and 53 percent had not heard of the 1619 Project. Among mothers of K-12 students, 38 percent said it was a “major concern” that there was “too much focus on race and racism” in their child’s school and another 30 percent said it was a “moderate concern.” But, among women more broadly, 40 percent said they “strongly agree” and another 27 percent said they “somewhat agree” that students should be taught about racial inequality. Those percentages dropped to 31 percent and 24 percent, respectively, when asked the same question about structural racism. Only 21 percent strongly agreed that it was appropriate for state legislatures to limit what can be taught about race and racism.

Seventy percent of the survey’s respondents were White, and among them, 45 percent of college-educated mothers with a K-12 student said it was “major concern” that there is too much focus on race and racism in their child’s school, and 28 percent of non-college educated mothers agreed. Thirty-eight percent of college-educated and 20 percent of non-college educated mothers said there was too little focus on events that were significant to Black Americans such as the Tulsa race massacre or Juneteenth.

It is not surprising that White Americans would hold muddled and sometimes contradictory views on race — and that terms and framing can have significant impacts on whether they support, for example, the teaching of racial inequality versus structural racism. The terms themselves have been the subject of education efforts.

Overall views on race among White Americans also shift — and policy shifts back and forth along with it.

Barack Obama, the first Black U.S. president, would often expand on civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.’s idea that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

“Progress will come in fits and starts,” Obama said in his 2012 reelection victory speech.

“It’s not always a straight line. It’s not always a smooth path,” he added.