It may not have seemed unusual when a protest in support of Black lives and against police brutality moved through the town of Pembroke, North Carolina, in late June and faced off with counterprotesters.

Krista Davis, CC BY-ND

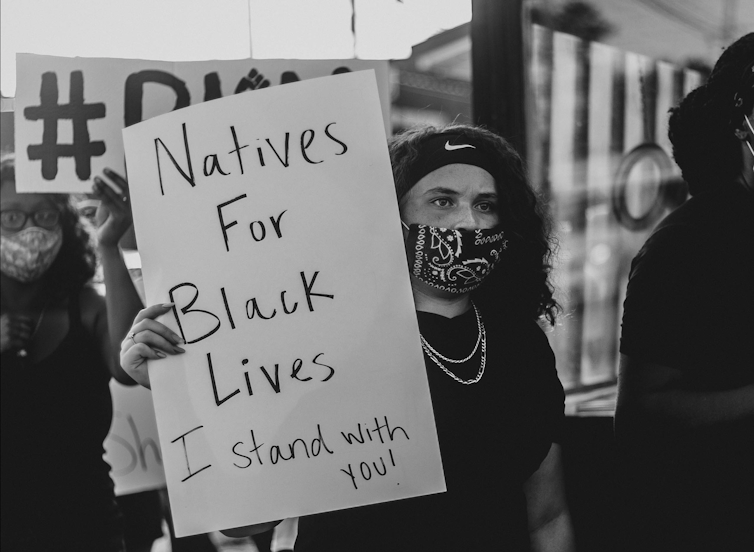

But it was unusual because of who was involved – on both sides. The march was organized by several students from the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, the state’s historically American Indian university.

Today, UNC Pembroke is recognized as one of the most ethnically diverse universities in the South. According to one witness, “the people who participated were very diverse” and included African American and Native American students.

The marchers were met by a group of counterprotesters who reportedly used racial slurs, threw beer and brandished rifles and knives in a stated attempt to “protect their property” from destruction.

The counterprotesters were mostly Lumbees, a state-recognized Native American tribe with about 55,000 enrolled members, of which I am one.

Pembroke, in Robeson County, is the seat of the Lumbee Tribe; Native Americans make up more than half of the town’s population. Some Lumbees marched too, in solidarity with their Black neighbors and relatives. Many Lumbees publicly lamented the attacks on the marchers.

In a letter published the following day in the local newspaper, Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery said, “Our ancestors did not fight for our lives only for us to turn around and abuse our neighbors, co-workers and family members.”

Krista Davis, CC BY-ND

Lowery and I both, as historians, saw 200 years of Lumbee history reflected in this encounter. It is a complex 200-year history of struggle, protest and resistance to white supremacy and its social effects, one shared by Indigenous and African Americans across the nation.

The Lowry War

Lumbees are no strangers to injustice. Beginning in the early 19th century, Native Americans in North Carolina suffered, as skin color became the determining factor for one’s status in society. In 1835, under the revised state Constitution, American Indians and other free people of color lost their right to vote.

In “a nation of white people,” as North Carolina lawyer and lawmaker James W. Bryan described it in 1835, all people of color – including American Indians – in North Carolina would be considered legally inferior.

After their disenfranchisement, Lumbees suffered legal and economic harassment and suppression for decades to come. Indians became increasingly antagonistic toward their white neighbors as oppressive policies such as “tied mule” incidents exploited Indian labor and confiscated Indian-owned land.

In addition, free people of color in North Carolina lost their right to own and bear arms in 1840, leaving many defenseless to attacks.

As the Civil War ripped the nation apart, hostilities between American Indians and white elites in Robeson County led to an eight-year guerilla war from 1864 to 1872 led by Indian vigilante Henry Berry Lowry and his “gang” of neighbors and kin.

The Lowry gang staged robberies and murdered proponents of white supremacy in violent protest of oppression. In response, Lowry and his associates were outlawed and sought after by bounty hunters.

Henry Berry Lowry vanished in 1872, his bounty was never collected, and no one knows his fate for certain.

Now, many Lumbees celebrated Lowry as a hero, while other Lumbees view him as a criminal, condemning his use of violence and lawlessness. Historian William McKee Evans wrote that Lowry’s legacy serves as a symbol of resistance, giving Indians in Robeson County “a new confidence that despite generations of defeat, revitaliz[ing] their will to survive as a people.”

Trouble for Indians did not end following the Civil War or the Lowry War. The decade following Reconstruction became informally known as the “decade of despair” for Lumbees. Despite the restoration of the Indian right to vote in 1868, the county witnessed violence against Indians and Blacks as the Ku Klux Klan made its presence known in southeastern North Carolina.

At the turn of the 20th century, Lumbees began their fight for recognition, not just as people of color but as Native Americans. Jim Crow laws affected them as well as African Americans, and American Indians resisted segregation, setting out to better their communities through education.

Routing the Klan

The Klu Klux Klan most famously entered the Lumbee story again in 1958. After the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision outlawing school segregation, Klan activity increased across North Carolina.

Klan leader James W. “Catfish” Cole targeted Lumbees, denying their Indigenous identity and accusing them of being mixed-race people, partly white and partly Black.

Cole staged two cross burnings in Robeson County, one to confront a Lumbee family who moved into a white neighborhood and another to threaten an Indian woman dating a white man.

On Jan. 18, 1958, a Klan rally was planned in Robeson County at Hayes Pond to “put Indians in their place.” Word spread quickly around the county, and the 50 Klansmen found themselves surrounded by 500 Lumbee men and 50 Lumbee women, armed with guns and knives. Lumbees fired their guns into the air, causing Cole and his followers to flee.

In this armed protest, Lumbees ironically used the same type of lawless behavior embodied by the Klan while taking the fight for justice into their own hands.

Just like the Lowry War, the legacy of the Lumbee routing of the Ku Klux Klan is complex. While “Catfish” Cole was charged for inciting a riot, many believed that the Lumbees were the aggressors, attacking the Klan’s right to free speech. Regardless, the Klan has not held a publicized rally in North Carolina in the more than 60 years since then – another victory for Indian resistance to white supremacy.

A common ground

Adolph Dial, the first scholar to write a comprehensive history on the Lumbees, recognized that in his lifetime, issues of injustices still pervaded the Lumbee community. He famously noted that to be a Lumbee is “to find some of one’s basic rights as an American and a human being restricted if not denied. Indeed, shorn of all frills, the history of the Lumbees is a history of struggle.”

Lumbees have a shared experience of pursuing justice even though there have always been disagreements about how to accomplish it.

In her responses to the protest on June 26, 2020, Lumbee scholar Malinda Maynor Lowery also wrote, “Black lives matter to Lumbees because we have a responsibility to account for our own racism if we are to ever achieve our goals as an American Indian nation.”

If the Lumbee struggle is truly one for justice, it would appear contradictory not to support that goal for our Black neighbors and family members, or worse – to participate in their oppression ourselves.

Krista Davis, CC BY-ND

In the conclusion to Adolph Dial’s 1975 book, “The Only Land I Know,” he wrote, “The problems of today plead for attention and demand answers … The question now is, what is to come?”

During present times of social unrest, the Lumbee narrative continues to serve as a reminder that history is complicated. Despite disagreements and contradictions, history is a record of shared pasts, shared struggles and shared pursuit of justice and reconciliation.![]()

Jessica R. Locklear, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Jessica R. Locklear, History Ph.D. Student, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/