The Baseball Writers’ Association of America recently announced that it would remove former Major League Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ name from the plaques awarded to the American and National League MVPs.

The decision came after a number of former MVPs, including Black award winners Barry Larkin and Terry Pendleton, voiced their displeasure with their plaques being named for Landis, who kept the game segregated during the 24 years he served as commissioner from 1920 until his death in 1944. The Brooklyn Dodgers ended the color line when they signed Jackie Robinson to a contract in October 1945, less than a year after Landis’ death.

Landis has had his defenders over the years. In the past, essayist David Kaiser, baseball historian Norman Macht, Landis biographer David Pietrusza and the commissioner’s nephew, Lincoln Landis, have claimed that there is no evidence that Landis said or did anything racist.

But in my view, it’s what he didn’t say and didn’t do that made him a racist.

In my book “Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball,” I argue that baseball’s color line existed as long as it did because the nation’s white mainstream sportswriters remained silent about it, even as Black and progressive activists campaigned for integration.

However those who ran the league possessed far more power than sportswriters. Landis, along with the owners, knew that there were Black players good enough to play in the big leagues. If he wanted to integrate Major League Baseball, he could have.

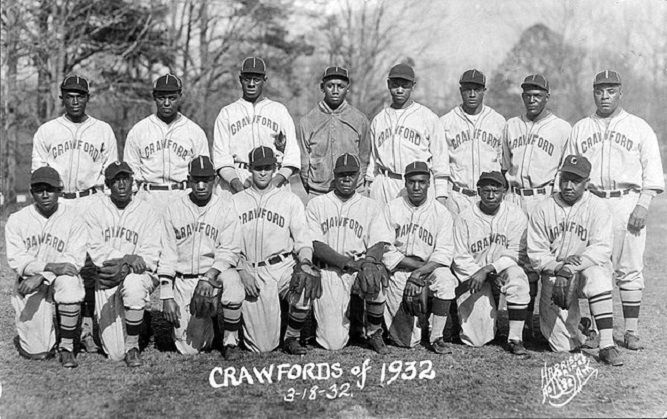

Instead, he did all he could to prevent the rest of America from knowing just how talented Black baseball players were.

Petitions go ignored

By the time Landis became commissioner in 1920, baseball had been segregated ever since a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement” took place among team owners in the 1880s.

However, it was common practice in the 1920s for Major League teams to earn extra money in the off-season by playing Black teams in exhibition games. Landis put a halt to these games because he wanted to end the embarrassment of the Black teams’ winning so often.

It is worth noting that Black athletes competed with white ones in other sports in the 1920s and 1930s, including boxing, college tennis, college football and, for several years, the National Football League. Black athletes also represented the United States in the Olympics.

During the 1930s, Black sportswriters like Wendell Smith and Sam Lacy, along with white sportswriters for the Communist newspaper The Daily Worker, intensely campaigned for the integration of baseball.

In their editorials and articles, Worker sportswriters chronicled the accomplishments of Negro League stars and told readers that struggling Major League teams could improve their chances by signing Black players. Meanwhile, Communist activists organized protests and circulated petition drives outside the ballparks of New York’s three Major League teams – the Yankees, Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers – demanding that teams sign Black players.

The petitions, which had, according to one estimate, a million signatures, were then sent off to the commissioner’s office. They were ignored. The Daily Worker regularly focused on Landis as the person responsible for the color line, while the Black press derisively called him “the Great White Father.”

Don’t ask, don’t tell

Landis’ defenders say that he could not possibly have been a bigot because he suspended Yankees outfielder Jake Powell for making a racist comment during a 1938 radio interview.

Landis suspended Powell not because the ballplayer used a slur, but because it was heard by fans, and Black activists pressured the commissioner to do something. While Landis ended up punishing a racist player, he did nothing to end racial discrimination against Black players.

Furthermore, Landis refused to allow players and managers to speak on the issue. When Brooklyn manager Leo Durocher was quoted in a 1942 Daily Worker article saying he would sign Black players if he were allowed to, Landis ordered Durocher to deny that he made the statement.

The following year, Landis again subverted the campaign to end segregation in the sport.

Sam Lacy, who was then working for the Chicago Defender, repeatedly asked Landis for a meeting to talk about the color line. When Landis finally agreed, Lacy asked the commissioner if he could make the case for integration at baseball’s annual meeting.

Landis, without telling Lacy, invited the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association. Also invited to speak was Paul Robeson, the onetime college football star who had become an actor, singer, writer – and avowed Communist. Lacy was incensed that Robeson would be asked to address the conservative white owners about the sensitive issue of integration.

To Lacy, the presence of Robeson meant that Landis could plant seeds of suspicion with white owners and sportswriters that the campaign to integrate baseball was a Communist front.

Lacy wrote in a column that Landis reminded him of a cartoon he had seen of a man extending his right hand in a gesture of friendship while clenching a long knife that was hidden in his left hand.

Landis died in December 1944, and Lacy finally got a chance to address team executives in March of the following year. Brooklyn Dodgers executive Branch Rickey ended up signing Jackie Robinson to a contract several months later, thus ending segregation in baseball.

Lee Lowenfish, Rickey’s biographer, was convinced that Landis would have tried to stop the Brooklyn executive from signing Robinson.

I believe it is no coincidence that baseball remained segregated during Landis’ reign as commissioner – or that it became integrated only after he died.![]()

Chris Lamb, Professor of Journalism, IUPUI

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/