It’s hard to imagine navigating modern life without a mobile phone in hand. Computers, tablets and smartphones have transformed how we communicate, work, learn, share news and entertain ourselves. They became even more essential when the COVID-19 pandemic moved classes, meetings and social connections online.

But few people realize that our reliance on electronics comes with steep environmental costs, from mining minerals to disposing of used devices. Consumers can’t resist faster products with more storage and better cameras, but constant upgrades have created a growing global waste challenge. In 2019 alone, people discarded 53 million metric tons of electronic waste.

In our work as sustainability researchers, we study how consumer behavior and technological innovations influence the products that people buy, how long they keep them and how these items are reused or recycled.

Our research shows that while e-waste is rising globally, it’s declining in the U.S. But some innovations that are slimming down the e-waste stream are also making products harder to repair and recycle.

Recycling used electronics

Thirty years of data show why the volume of e-waste in the U.S. is decreasing. New products are lighter and more compact than past offerings. Smartphones and laptops have edged out desktop computers. Televisions with thin, flat screens have displaced bulkier cathode-ray tubes, and streaming services are doing the job that once required standalone MP3, DVD and Blu-ray players. U.S. households now produce about 10% less electronic waste by weight than they did at their peak in 2015.

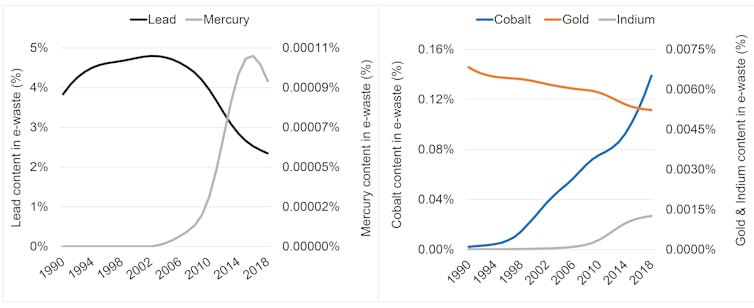

The bad news is that only about 35% of U.S. e-waste is recycled. Consumers often don’t know where to recycle discarded products. If electronic devices decompose in landfills, hazardous compounds can leach into groundwater, including lead used in older circuit boards, mercury found in early LCD screens and flame retardants in plastics. This process poses health risks to people and wildlife.

There’s a clear need to recycle e-waste, both to protect public health and to recover valuable metals. Electronics contain rare minerals and precious metals mined in socially and ecologically vulnerable parts of the world. Reuse and recycling can reduce demand for “conflict minerals” and create new jobs and revenue streams.

But it’s not a simple process. Disassembling electronics for repair or material recovery is expensive and labor-intensive.

Some recycling companies have illegally stockpiled or abandoned e-waste. One Denver warehouse was called “an environmental disaster” when 8,000 tons of lead-filled tubes from old TVs were discovered there in 2013.

The U.S. exports up to 40% of its e-waste. Some goes to regions such as Southeast Asia that have little environmental oversight and few measures to protect workers who repair or recycle electronics.

Disassembling products and assembling data

Health and environmental risks have prompted 25 U.S. states and the District of Columbia to enact e-waste recycling laws. Some of these measures ban landfilling electronics, while others require manufacturers to support recycling efforts. All of them target large products, like old cathode-ray tube TVs, which contain up to 4 pounds of lead.

We wanted to know whether these laws, adopted from 2003 to 2011, can keep up with the current generation of electronic products. To find out, we needed a better estimate of how much e-waste the U.S. now produces.

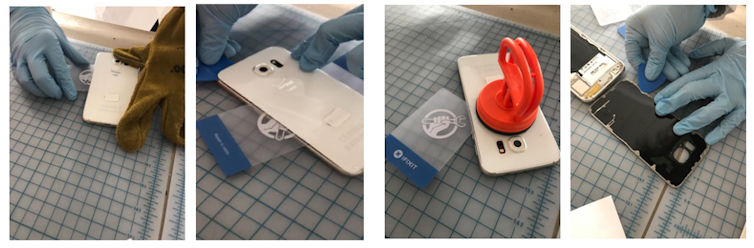

We mapped sales of electronic products from the 1950s to the present, using data from industry reports, government sources and consumer surveys. Then we disassembled almost 100 devices, from obsolete VCRs to today’s smartphones and fitness trackers, to weigh and measure the materials they contained.

Shahana Althaf, CC BY

We created a computer model to analyze the data, producing one of the most detailed accounts of U.S. electronic product consumption and discards currently available.

E-waste is leaner, but not necessarily greener

The big surprise from our research was that U.S. households are producing less e-waste, thanks to compact product designs and digital innovation. For example, a smartphone serves as an all-in-one phone, camera, MP3 player and portable navigation system. Flat-panel TVs are about 50% lighter than large-tube TVs and don’t contain any lead.

But not all innovations have been beneficial. To make lightweight products, manufacturers miniaturized components and glued parts together, making it harder to repair devices and more expensive to recycle them. Lithium-ion batteries pose another problem: They are hard to detect and remove, and they can spark disastrous fires during transportation or recycling.

Popular features that consumers love – speed, sharp images, responsive touch screens and long battery life – rely on metals like cobalt, indium and rare-earth elements that require immense energy and expense to mine. Commercial recycling technology cannot yet recover them profitably, although innovations are starting to emerge.

Reenvisioning waste as a resource

We believe solving these challenges requires a proactive approach that treats digital discards as resources, not waste. Gold, silver, palladium and other valuable materials are now more concentrated in e-waste than in natural ores in the ground.

“Urban mining,” in the form of recycling e-waste, could replace the need to dig up scarce metals, reducing environmental damage. It would also reduce U.S. dependence on minerals imported from other countries.

Government, industry and consumers all have roles to play. Progress will require designing products that are easier to repair and reuse, and persuading consumers to keep their devices longer.

We also see a need for responsive e-waste laws in place of today’s dated patchwork of state regulations. Establishing convenient, certified recycling locations can keep more electronics out of landfills. With retooled operations, recyclers can recover more valuable materials from the e-waste stream. Steps like these can help balance our reliance on electronic devices with systems that better protect human health and the environment.

Callie Babbitt, Rochester Institute of Technology and Shahana Althaf, Yale University

Callie Babbitt, Associate Professor of Sustainability, Rochester Institute of Technology and Shahana Althaf, Postdoctoral associate, Yale University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.