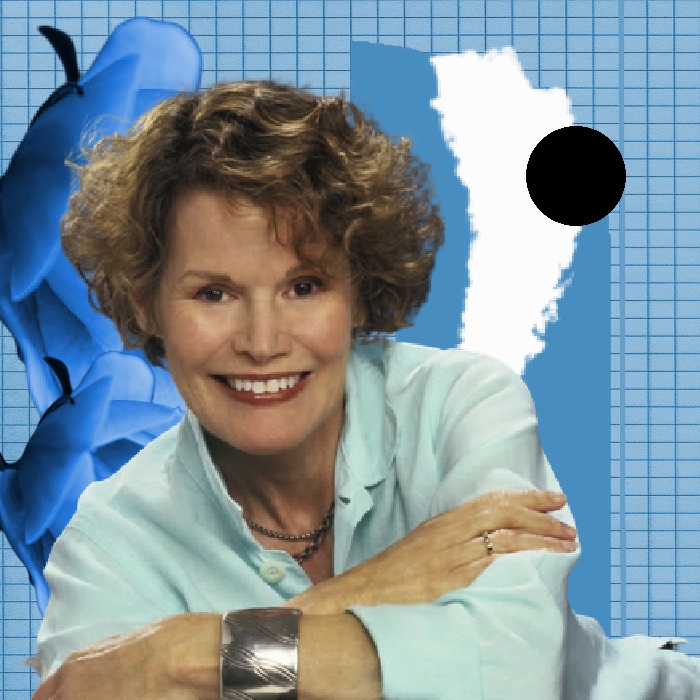

Judy Blume is having a moment. A staple of backpacks of elementary, middle grade and young adult readers since the 1970s, Blume, 85, is about to see her stories on the big screen. The new documentary “Judy Blume Forever” debuts on Amazon Prime on Friday after premiering to rave reviews at the Sundance Film Festival in January. And on April 28, the first-ever film adaptation of Blume’s 1970 classic “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” releases in theaters, bringing “We must! We must! We must increase our bust!” to a whole new generation.

Blume’s work is beloved by children and teens — and the adults they one day become — for its frank depictions of the day-to-day realities of growing up. They grapple with puberty, masturbation and sex on top of the emotional journey, subjects glossed over or ignored in many sex ed classes in schools.

This recognition of Blume’s legacy and work comes as book bans in schools have increased over the past year. A report from PEN America found that in the 2021-2022 school year, over 2,500 individual books were stripped from school library shelves. Blume’s titles are constants on the American Library Association’s list of frequently banned books for children and young adults. For experts who study literary education and young adult literature — who are in the trenches of the work to fight school book bans — the celebration of Blume is a recognition of that there is value in depicting the messy parts of growing up that some adults won’t acknowledge. Those kinds of subjects are often epitomized by the books at the top of the most-banned lists.

Chris Finan, the executive director of the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), is no stranger to book bans or Blume, who has worked with the organization since she found herself at the center of the first significant national effort to ban books from schools in the 1980s.

“There’s always book banning going on in America,” Finan said. “This is not a new and novel phenomenon by any stretch of the imagination.”

In a typical year, there are anywhere from 300 to 500 challenges to individual titles in libraries, he said. These numbers began to spike upwards in the 1980s, when religious groups made pro-decency and anti-pornography campaigns the centerpiece of their political work.

Many of Blume’s books became targets. “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” openly discusses periods and centers a middle school girl trying to figure out her own relationship to God; “Blubber” includes mention of masturbation; “Forever” depicts two high school seniors making the choice to engage in their first sexual experience together. Many school districts removed Blume’s titles from their shelves in the wake of these bans — and the pushback to her books hasn’t slowed down. “Forever” was just banned from one Florida school district again last month.

As a result of these attacks against her books, Blume joined the board of the NCAC, becoming one of the foremost voices in the neverending fight against censorship that targets books for younger readers.

Due to the onslaught of attacks on books in the 1980s that were seen by censorship advocates as indecent — with Blume’s titles often at the center, Finan said — systems were eventually established for reviewing challenged books. Most books that are challenged in a typical year are ultimately kept in libraries because of this review process, Finan said.

What has changed with this most recent push for bans is that many challenged books — often written by LGBTQ+ people or people of color — are pulled from shelves before they can be reviewed. Ultimately, this has yielded a situation that Finan describes as one where “millions of kids have lost access to really important books.”

“This is the most we’ve seen of book challenges and book bans since the 1980s, which was around the satanic panic,” said Emily Knox, an associate professor of information studies at Rutgers. “We’re just in a really reactionary time.”

There are common threads in the books that are often pulled from shelves, Knox noted: Books centering race, LGBTQ+ issues or mental health are often targeted.

“Because these are voices that are usually marginalized and there has been a push to decenter White heterosexual male voices in the canon, this is the reaction today and we shouldn’t have been very surprised about it. Because this is what is always the reaction to messing with the status quo,” she said.

The work of Blume, who is White, shares commonalities with the modern books that are frequently banned today, Knox said.

“She centers people who are not necessarily White, who are often Jewish, people who are not usually who we think about as the universal subjects for literature,” Knox said.

Blume’s books are still considered trailblazing for the way they talked about burgeoning sexuality without judgment, and the everyday lives of young people as complicated, difficult and worthy of attention, experts said. The same could be said of so many of the books routinely censored today. The book ban surge in school districts across the country “can be depressing on any given day,” Finan said. Which is why, he stressed, Blume matters so much right now.

“It should give people some reassurance that what happened when Judy Blume was attacked and they tried to purge their libraries of her titles, Judy Blume did not give into that pressure,” he said. “She didn’t stop writing books. She didn’t stop writing about the issues that she wanted to write about. She fought back and was joined by teachers and librarians and parents and students who protested the censorship.”

Kelly Fremon Craig, the director of the forthcoming “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” film adaptation, said she started reading Blume when she was 11 and fell in love. “She was writing about what it was really like to be a girl at that age. She was telling the truth and including all the embarrassing details,” Fremon Craig said, saying Blume was why she wanted to become a writer and filmmaker.

“She was the first person to do that profound thing that writers have done to me for years which is to tell me in some way that I’m not alone. … Some writers have become lifelines to me, and Judy Blume was absolutely the first one.”

After her film “The Edge of Seventeen” debuted to critical acclaim for its embrace of the difficulties of being a teen girl, Fremon Craig said she felt “an enormous amount of pressure” to figure out what her next project would be. She started to compile a list of the authors who had influenced her most in her career, prompting her to reread “Margaret” for the first time since childhood. Fremon Craig was struck by the way Blume depicted her protagonist’s journey through puberty and existential feelings of spiritual searching.

When Blume gave her the green light to adapt “Margaret,” Fremon Craig started to reckon with the consistent place the title holds on banned book lists — and why people get so concerned when kids speak honestly about their bodies and interior lives. The way that “Margaret” is frequently banned because of its frank, and central, discussion of menstruation was always top of mind for Fremon Craig.

She pointed to the scene in her movie in which Margaret buys a box of maxi pads before even getting her own period, then puts a pad in her underwear, trying on the physical element of the pad and the thrill of adulthood as she parades around her room. While shooting that scene, Fremon Craig remembered doing the same thing herself as a girl.

“There was something so emotional about it, because by showing it we were saying, ‘This is normal. We all do this. It’s okay. You don’t have to be embarrassed about it and you don’t have to hide it,’” she said.

Ahead of the film’s release, she’s also thinking about the proposed Florida law that would ban any discussion of menstruation in schools until the sixth grade and what happens to the young people who may get their periods — or read “Margaret” — before then.

“It’s the absurdity that’s so hard for me to wrap my head around,” Fremon Craig said. “I have been really asking myself — why, why can’t we talk about something that half the population goes through?”

Fremon Craig recalled talking to a room full of men agents and film executives about the project, having to regularly say the words “period” and “maxi pads” in front of them and finding herself feeling embarrassed at first.

“Then I thought to myself, ‘That is wrong that I feel embarrassed to say this. It is wrong that as an adult woman I have purchased tampons and tried to avoid eye contact, find a female cashier, whoever looks the friendliest. What is that about?’”

Fremon Craig found her answer in the process of getting to work so intensely with one of Blume’s most beloved texts: The very thing that continues to make so many people uncomfortable are the very subjects in need of attention, tenderness and a lack of shame.

“The thing Judy Blume does so beautifully is she writes with absolute freedom and honesty. She tells the truth. She tells it like it is. And oddly enough, sometimes the truth feels like it’s in short supply,” Fremon Craig said. “There’s been a lot of glossing over because the truth is messy and complicated and she, for decades, has been willing to say it all and have no shame about any of it. I hope that continues and that it continues to provoke more work like that where more people say, ‘Here is my honest experience.’”

It’s that honesty that has separated Blume from her peers, said E. Sybil Durand, an associate professor of young adult literature at the University of Arizona.

“She’s one of the early writers who really captured a young person’s voice and really focused on their experience and not an idealized version of childhood that adults think about or like to talk about, but the real shame and challenges that children are concerned about,” Durand said.

Children’s literature before Blume focused on “what adults wanted and expected out of young girls and boys,” Durand said. “They were very didactic.” What Blume did that was so revolutionary was resist the notions of how adults perceive children.

Blume’s books have in a way modeled the primary underlying symptom of book bans today, Durand said, which is “that childhood is socially constructed, and that the community is the one that sets the rules for what it means. There’s a gap between how children actually experience life and how adults imagine childhood should be.”

Davina Pardo, one of the co-directors of the documentary “Judy Blume Forever,” said Blume’s concern with disrupting the notion of the ideal childhood came up a lot during filming.

“One of the things that Judy very often says is that both banning and censorship come from a place of fear, of wanting to control children, and to hurt — which is of course so counter to the work she’s been doing her entire life, which is all about trusting children,” Pardo said.

The American Library Association maintains lists of the most challenged books each calendar year; the most recent list from 2021 is dominated by titles that have “LGBTQIA+ content” and are “considered to be sexually explicit.” Topping the list is the autobiographical graphic novel “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe, in which the author tries to explain to their family what it means to be nonbinary and asexual.

Many challenged books also often tackle racism, as in “The Hate U Give,” Angie Thomas’ debut novel inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, tells the story of a 16-year-old girl who witnesses the shooting of her childhood best friend by a police officer.

As she looks at book bans across the country, Pardo thinks of something that Jason Reynolds, a Black author of bestselling and frequently challenged young adult books, says in the documentary: “If you want to understand what conversations are happening in this country when tensions are bubbling to the surface, look at the banned books list. It’s such a reflection of what anxieties are happening right now.”

Balancing the celebration of Blume’s work with the fact that it has been so challenged is a central thread of the documentary from Pardo and co-director Leah Wolchok.

“When the right-wing forces that were pushing back against Judy were afraid, it was post-Roe, a reaction to post-feminism and books that were honoring female sexuality were scary. That was the pushback that Judy experienced,” Pardo said. “I think some of those same forces are today pushing back on what’s now considered scary or hasn’t been accepted by a segment of our population and that’s racism and it’s that people are talking about gender in a new way.”

Knox said that increasingly, the conversation surrounding book bans today focuses on parental rights and whether children have the right to read things that would expose them to “the difficulties of life” or whether those conversations should happen only at the choice of a parent. So much of this sentiment can be summarized by why people have bristled at Blume’s books.

The way people talked about Blume’s books about periods and masturbation in the past is incredibly similar to the way that transgender kids identities, lives, and agency are being talked about in statehouses and school board meetings nationwide today — especially when it comes to limiting access to books that validate and reflect their own lived experiences.

“The point is really to not allow people to be able to discuss how they feel about themselves, to not give them the words to communicate, ‘I am uncomfortable in my body’ and I think that’s why a lot of these books are so important,” Knox said. “These are books being written in the same naturalistic style that Judy Blume was writing in also.”

“What is most important about her work today is what continues to be important about these books, which is that you have to give kids autonomy and vocabulary to be able to talk about themselves and what they are going through,” she continued. “If you can’t describe your life, you have no agency and that is actually part of the point”

But as Durand pointed out, even as Blume received pushback, she still pushed forward writing on the very things that she knew existed in young people’s lives. Even if some adults didn’t want to see her write about the realities of childhood, they still existed. Durand sees that today in book bans targeting works centering race or LGBTQ+ issues.

Wendy Jean Glenn, a former classroom teacher and a professor of literacy at the University of Colorado-Boulder, stressed that Blume’s books are tools for teaching empathy within the context of interpersonal relationships that feels especially pertinent today.

“There’s something really powerful about learning how to understand the perspectives of someone else in your classroom, to feel empathetic when somebody might be hurting. If we think about the sometimes complicated realities of relationships in schools, I think Judy Blume stories provide opportunities to invite real conversation around how it could look to stand up and advocate for a friend or even somebody you don’t know very well when you see something not right happening. I think that those seeds are timeless.”

That empathy is crucial in the continued fight back against censorship and understanding that even if the books focusing on LGBTQ+ youth and youth of color are banned, it won’t stop the people they are trying to center from existing.

“These young people are still there,” Durand said. “They’re in schools. They’re alive. They have their identities.”

Insisting on the importance of access to the words that describe young people’s actual experiences is why Blume’s work continues to matter to readers, and why her triumphs against decades-worth of censors does too, Finan said.

“I think a lot of people look up to her and admire her and recognize that they have to do what she has done and that they have to speak up. And they are speaking up. We see authors defending not only their own books but the other books that have been challenged,” Finan said. It’s why he describes Blume as “incredibly important not only as a person but as a symbol of resistance. She’s a great symbol that the truth will always prevail.”

He concluded, “People aren’t going to back down from these challenges and the fact that now she’s one of the most celebrated people of the year? She’s got the documentary, she’s got the film — she’s won. She took on the censors and she won.”

Originally published by The 19th