Nattie’s metaverse romance began with anonymous texting. At first “C” would admit only to living in a nearby town. Nattie eventually learned “Clem” was a man with a solitary office job like hers. For Nattie “lived, as it were, in two worlds” – the world of office tedium and an online world where “she did not lack social intercourse.”

Texting drew them closer: “annoyances became lighter because she told him, and he sympathized.” Nattie soon realized “she had woven a sort of romance about him who was a friend ‘so near and yet so far’.” Their blossoming relationship almost failed when Clem’s co-worker visited Nattie’s office pretending to be Clem, but the deceit was exposed in time for their “romance of dots and dashes” to succeed.

With that last sentence I gave away the ending to “Wired Love,” source of the quotes above. Published in 1879, Ella Thayer’s novel of “the telegraphic world” makes remarkable predictions. Yet “Wired Love” is planted firmly during the time of what journalist Thomas Standage aptly termed the “Victorian Internet.” Many aspects of the current metaverse were already familiar 143 years ago.

What’s old is new

History is more than fun facts: It deeply shapes ways of thinking and acting. As an anthropologist who’s been studying virtual worlds for almost two decades, I’ve found that the metaverse’s rich past shapes what too often appears unprecedented.

This isn’t accidental. The contemporary metaverse is overwhelmingly owned and developed by corporations whose profit models demand focus on the Next Big Thing. This typically sidelines history – with massive financial and social implications.

At its core, the metaverse is defined by the concept of the virtual world. As “Wired Love” illustrates, the telegraph and later the telephone constitute early virtual worlds.

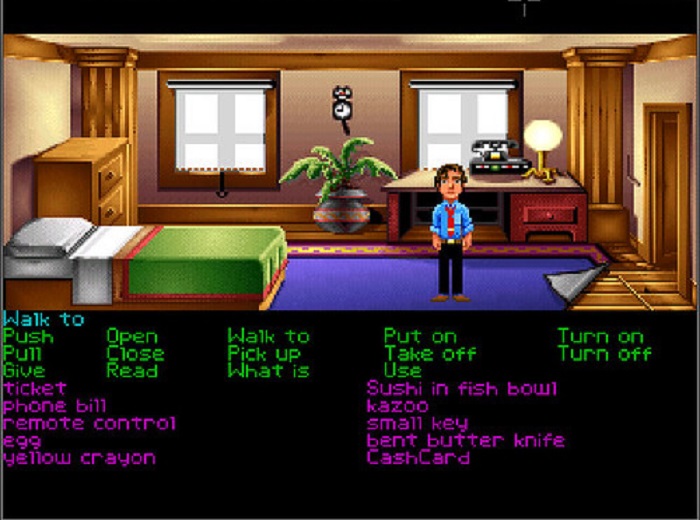

Multi-user dungeons, or MUDs, arose in the second half of the 20th century. These virtual worlds appeared on local computer networks in the late 1970s, and entered dial-up internet services in the 1980s and 1990s. Richard Bartle, co-creator of the first MUD, noted that by 1993 over 10% of all internet traffic was on MUDs. Virtual worlds with graphics, including avatars, date back to Habitat, launched in 1985.

With advent of broadband in the 2000s, many key aspects of the contemporary metaverse became established. Longtime metaverse observers like Wagner James Au have repeatedly emphasized how many “new” developments have rehashed long-standing debates.

Real estate and the laws of virtual physics

Consider what metaverse history reveals about virtual real estate. Pundits enthuse about the virtual “land rush” and emphasize location. For instance, virtual world The Sandbox sells plots for around $2,300, but in December 2021 someone paid $450,000 to purchase land next to a virtual mansion owned by rap star Snoop Dogg.

Why the price spike? Co-founder Sebastien Borget explained that The Sandbox has a finite number of plots, and people can access only adjacent plots. Thus, only a few people can own virtual land next to Snoop Dogg.

I believe that The Sandbox is deeply indebted to the virtual world Second Life, where spaces to practice building have been termed “sandboxes” since its 2002 launch.

Second Life originally had “point-to-point teleportation” (P2P). You could arrive anywhere in an instant. But in 2003 Linden Lab, the company that owns Second Life, disabled P2P. Residents trying to reach a destination would appear at the nearest “telehub.”

This had implications for real estate. Valuable for businesses and entertainment, plots of land near telehubs sold for top dollar — until 2005, when Linden Lab suddenly announced the end of telehubs and the return of P2P.

Land near former telehubs no longer had special value; some people lost thousands of dollars. The most powerful landlord can’t change the laws of physics, but Linden Lab could literally recode scarcity out of existence.

Fast-forward almost 20 years. Land next to Snoop Dogg’s virtual mansion is scarce: A plot could cost $450,000 because The Sandbox doesn’t have P2P. But were the company to suddenly add P2P, that $450,000 investment could become nearly worthless. That pundits have tended to ignore this fact reveals the danger of forgetting metaverse history.

Immersion – sensory or social?

Another example of metaverse history’s importance concerns the idea of virtual environments. Virtual worlds don’t just connect places; they’re places in their own right.

People played chess using the telegraph 150 years ago; those virtual chessboards weren’t located on either end of the wire. In 1992 Bruce Sterling noted that telephone calls don’t take place in your phone or in the other person’s phone. They take place in a virtual environment: “The place between the phones. The indefinite place out there, where the two of you, two human beings, actually meet and communicate.”

In 1990, Habitat’s founders concluded that the metaverse is defined more by the interactions among people within it than by the technology that creates it. They were particularly skeptical of virtual reality technologies, noting “the almost mystical euphoria that currently seems to surround all this hardware is, in our opinion, both excessive and somewhat misplaced.”

At issue isn’t VR’s potential, but the Matrix-like idea that sensory immersion is necessary to the metaverse in every instance. The key distinction is between sensory immersion and social immersion. The idea that virtual environments require VR misunderstands “immersion.” It’s also ableist, since not everyone can see or hear. The metaverse’s history indicates that social immersion is the metaverse’s foundation.

Learning from history

The metaverse has a long way to go, but it already has a long history. Proximity and immersion are just two examples of crucial topics this history can demystify.

This is important because the current, rampant mystification isn’t accidental. The emerging version of the metaverse is overwhelmingly owned and developed by Big Tech. These companies seek to manufacture the perception that the metaverse is new and futuristic. But metaverse histories are real; they can reveal past mistakes and contribute to better virtual futures.![]()

Tom Boellstorff, University of California, Irvine

Tom Boellstorff, Professor of Anthropology, University of California, Irvine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.