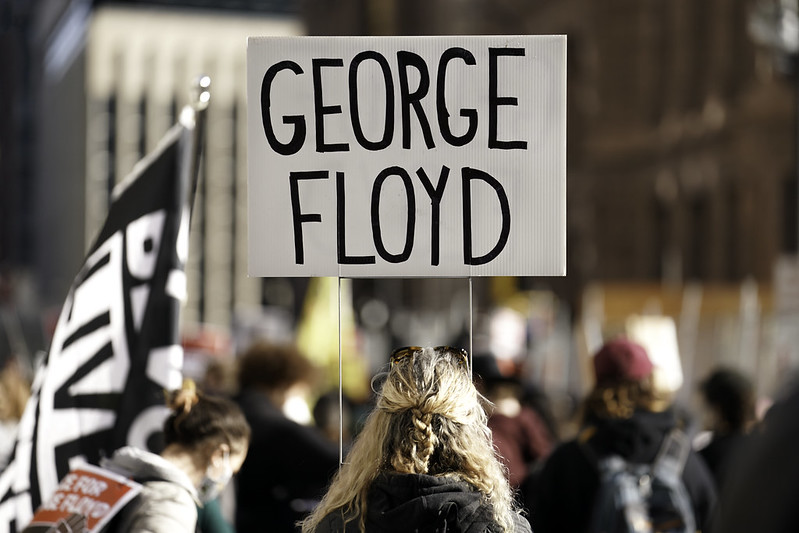

When 17-year-old Darnella Frazier started recording video of Minneapolis policeman Derek Chauvin murdering George Floyd, she initiated a series of historic events that led to Chauvin’s conviction.

But for all the discussion of technology following her actions – how cellphones enable video recording of police abuse and how social media encourages instantaneous mass distribution – the key factor in George Floyd’s name becoming globally famous may not be Frazier’s cellphone. It may not even be social media.

It was the culture and tradition of U.S. civil liberties and media freedom that played an essential role in protecting Frazier’s ability to record and retain possession of the video, and the capability of commercial corporations to publish it.

Had the same events transpired in China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Singapore or elsewhere, nobody might ever have learned of Floyd’s fate.

The constitutional protections enjoyed by U.S. citizens empower and encourage everyday Americans to discover, record, expose and distribute evidence of governmental malfeasance. This freedom to publicize crimes committed by state actors creates the possibility of improving policing and making the administration of justice more sensitive, effective and responsive.

But it also threatens to undermine state authority, which is why so many U.S. politicians remain wary of such freedoms.

To understand how the United States developed this unconstrained news culture, you need to return to Minneapolis, to a moment one century ago, when a newspaper exposed police corruption and provided a key turning point in protecting the American public’s right to expose governmental crimes.

Press abuse vs. press limits

Jay Near always knew there were bad cops in Minnesota.

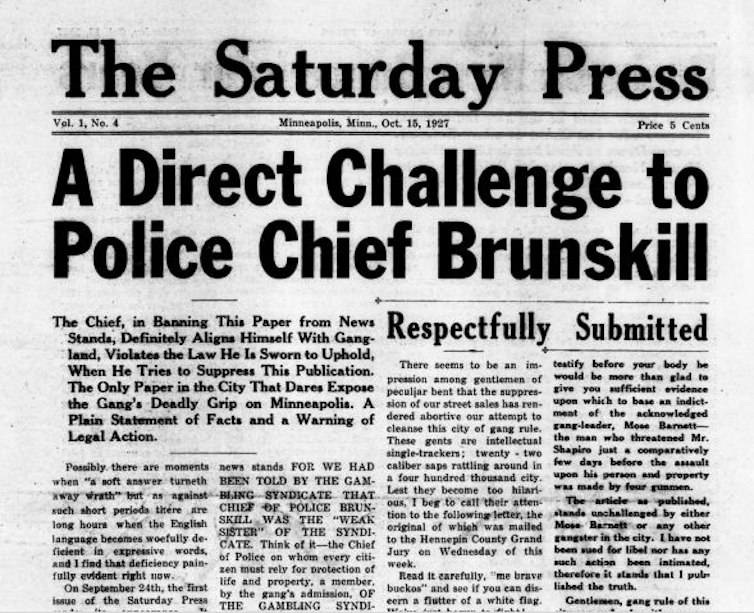

The publisher wrote about them in The Saturday Press, his Minneapolis newspaper. But Near called the cops “gangsters,” and he railed against what he claimed was a Jewish cabal controlling Minneapolis. Jay Near was a racist crank who published baseless conspiracy theories.

Today, Near is remembered – if at all – for his legendary Supreme Court victory in the 1931 U.S. Supreme Court decision known as Near v. Minnesota.

In 1927, Near and his business partner were prevented from publishing because The Saturday Press was deemed in violation of Minnesota’s “Public Nuisance Law.” That law outlawed publishing or circulating “obscene, lewd, and lascivious” or “malicious, scandalous and defamatory” materials.

Near sued to lift the prohibition, and his case made it to the Supreme Court, where his publication rights were ultimately vindicated. Near v. Minnesota opened up the modern version of press freedom we recognize today. Calling the Minnesota Public Nuisance Law “the essence of censorship,” a five-justice majority struck it down.

Essentially, the high court ruled that the U.S. Constitution allowed the abuse of press freedom in order to protect the most vibrant and robust public discussion possible. The Court had no illusions – the judges were well aware The Saturday Press published inflammatory misinformation. But in assessing the costs of censorship versus the benefits of liberty, the majority sided with the racist crank against the state of Minnesota.

Making the connection

The expansive media freedoms originating in the First Amendment, and later enshrined in Supreme Court decisions like Near v. Minnesota, would continue into the internet age with Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. That’s the law that allows people to post freely on internet sites while protecting the internet companies from legal jeopardy caused by those materials.

So, for example, defamatory accusations, negligent misrepresentation, intentional nuisance, dangerous misinformation and even content intended to incite emotional distress can be posted without Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or other companies being sued or held civilly liable.

For better or worse, Section 230 establishes media freedom across the internet in the U.S. And it is this law, built on the traditions of media freedom, that allowed Darnella Frazier – and all citizens who follow in her footsteps – to stand up to the government in ways previously unimaginable.

Minnesota Historical Society

But some stand ready to abandon these long-established legal and cultural protections.

Had Minnesota’s Public Nuisance Law survived Near’s challenge, it very well might have prevented publication of Frazier’s video. Those images could easily have been deemed “obscene,” or a “malicious” or “scandalous” incitement to violence.

But U.S. states can’t outlaw media organizations as “public nuisances.” Yet tensions over media freedom now exist that have the potential to lead to limits on the public’s ability to record and distribute police crimes.

Joe Biden and Donald Trump don’t agree on much, but one idea they have both publicly endorsed is eliminating Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996.

Critics who want to get rid of Section 230 regularly blame it for the plethora of “fake news,” misinformation, and hate speech that infects our web and social media. Because Twitter, Facebook, Tik Tok and others can’t be held liable for users’ content, the companies have felt little pressure, until recently, to moderate the blizzard of material they publish every second.

The cost of limiting the press

But media freedom is always a double-edged sword. Without Section 230 protection, social media companies would likely behave cautiously to minimize even the hint of legal jeopardy. Frazier’s video, in such a world, might be deemed too risky to distribute.

The immunity provided by Section 230 encourages YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and others, to stimulate users to post pretty much any news, information or video their users deem newsworthy or interesting.

The repeal of Section 230 could result in a system in which inflammatory or provocative news or images that might outrage or incite people could be deemed too socially destructive or disturbing of the peace by internet companies. And this could include images and video such as the murder of George Floyd.

The media freedom secured by Jay Near when he sought to expose police corruption in Minneapolis eventually assured the conviction of a criminal Minneapolis policeman.

The idea that U.S. citizens can report, publish, print and disseminate information that might be terribly damaging to authority is a radical one. Even within the United States, this freedom is often considered too expansive. In Oklahoma, for example, a new bill criminalizing the filming of police officers recently passed both houses of the state legislature, and elsewhere the rights of citizens and journalists to record police behavior occurring in public are regularly violated.

The direct line from Minneapolis in the 1920s to Minneapolis in the 2020s is the notion that protecting people’s rights promises to foster an active, aware and engaged citizenry – and that violating those rights by repressing or censoring information is deeply anti-American.

![]() Michael J. Socolow, University of Maine

Michael J. Socolow, University of Maine

Michael J. Socolow, Associate Professor, Communication and Journalism, University of Maine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Internet freedom around the world, and some great infographics. Additional Resource!