In 1517, the German theologian Martin Luther nailed 95 theses to Wittenberg’s Castle Church door, attacking indulgences, a Catholic practice that, according to church teachings, can reduce or eliminate punishment for sin. Starting in the 11th century, the church offered indulgences to those who joined the Crusades and later sold certificates of indulgences to raise funds, giving rise to the abusive marketing tactics criticized by Luther.

Many people assume that the Catholic Church stopped granting indulgences after Luther’s famous rejection of them. Indeed, nearly 50 years later, Pope Pius V put a stop to their sale. However, Pius V also affirmed the validity of indulgences themselves so long as no money was exchanged. By 1563, he had endorsed a comprehensive doctrine on indulgences that emerged from a series of meetings with high-ranking clergy, called the Council of Trent.

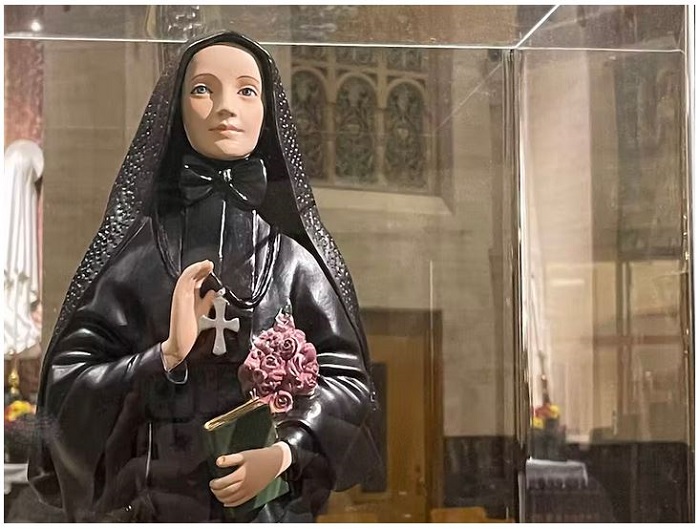

This comprehensive doctrine, revised in 1967 by Pope Paul VI, remains one of the church’s teachings to this day. For example, from November 2021 to November 2022, the National Shrine of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini in Chicago offered indulgences. It did so to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the canonization of Mother Cabrini, the first American citizen to be declared a saint, revered by Catholics for her work with fellow Italian immigrants to the United States.

While some Catholics welcome the granting of indulgences as an opportunity to reduce punishment for sin, others are unconvinced and dismissive; two other branches of Christianity, Protestantism and Eastern Orthodoxy, unequivocally reject this practice.

As a scholar of religious thought and author of a book of constructive theology focused on ideas of God, I am aware that the practice of indulgences is ancient, evolving and controversial within Catholic circles and beyond.

The doctrine of original sin

A fundamental doctrine of the Catholic Church is that all human beings are born with the stain of original sin as a result of Adam and Eve’s defiance of God in the Garden of Eden. This view, advanced by St. Augustine of Hippo in the third century, is one of the oldest teachings of the church. Because of original sin, no one, Augustine argued, can avoid sin without the assistance of God.

The faithful must cooperate with God’s freely given help, or grace, to heal the stain of sin. Still, according to Augustine and the church, regardless of effort, they are likely to sin again.

To sin, Pope Paul VI wrote, is to transgress the moral law and show “contempt for or disregard … the friendship between God and man.” Since sin is understood as rejecting God’s love, it deserves infinite separation from God after death: in other words, banishment to hell.

Forgiveness and reconciliation with God

The church has evolved a process for the forgiveness of sins, enabling Catholics to return to a state of friendship with God and offering them a reprieve from eternal punishment. This requires several steps, which together are called the sacrament of reconciliation.

For the sacrament to be effective, Catholics must feel true sorrow for their sins (contrition), admit their sins to a priest (confession) and promise to perform works of charity and seek sincere inner change (penance). Works of charity, chosen by the confessor priest, may include saying the Lord’s Prayer, saying a prayer to the Virgin Mary, and reciting the Nicene Creed, a fourth-century statement of Christian faith. These devotions are intended to turn the believer’s heart toward God.

After a person confesses their sins, the priest, through whom God is believed to speak, ritually grants forgiveness, saying “I absolve you.” The sacrament of reconciliation, according to the church, allows sinners to restore their friendship with God and releases them from the burden of guilt and the penalty of infinite punishment in hell.

The church teaches that even when a person has been ritually forgiven, God’s justice still requires some punishment to purge the sin – at the very least, suffering and miseries on Earth. Moreover, the church teaches, these hardships are to be welcomed because they purify the soul and heal the stain of original sin.

The doctrine of indulgences is rooted in the Catholic doctrine of punishment due after the forgiveness of sins and emerged as a means to ease the burden of this punishment. As early as the sixth century, Catholic priests in Ireland assigned difficult penitential works like pilgrimages to faraway Jerusalem, but some began to adjust these works based on an individual’s ability to bear them.

Reducing or eliminating punishment for sins

The substitution of easier works, however, does not meet God’s just demand for punishment of sin, according to the church. When an indulgence is granted, the pope satisfies the unmet demand for punishment by drawing from the church’s so-called treasury of merits. The merits in this treasury are believed to be infinite because they include the merits offered by Christ through his redemptive work on the cross as well as merits earned by the Virgin Mary and the saints.

This doctrine was codified in the late Middle Ages, in 1343, by Pope Clement VI.

By the time of Luther, certificates of indulgences were being sold to raise money on behalf of important patrons like the pope, who needed funds to build St. Peter’s Basilica. The priests who peddled these certificates preyed on faithful believers who feared punishment not just for themselves but also for loved ones who had died.

Terror over the fate of the dead stemmed from the church’s long-standing belief that if punishment for sin is not completed in this life, it continues after death when the soul departs for a spiritual place called purgatory. The soul must fully satisfy the punishment required by God’s justice before it can leave purgatory, come before God and enter heaven. The church has never claimed it could exercise authority over purgatory, the realm of God, to reduce punishment, but unscrupulous priests claimed indulgences could help the dead.

The current practice of seeking indulgences

Today, Catholics may seek indulgences for dead relatives in the same way they seek indulgences for themselves. But they are then limited to praying that Christ or the saints intervene on behalf of their loved ones so that these indulgences may count toward reduced punishment.

In his 1967 Indulgentiarum Doctrina, Pope Paul VI summed up this teaching: “If the faithful offer indulgences in suffrage for the dead, they cultivate charity in an excellent way and while raising their minds to heaven, they bring a wiser order into the things of this world.”

The church offers indulgences under specific conditions. Besides visiting designated holy sites such as the National Shrine of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini during set periods of time and for special occasions, Catholics can receive indulgences by reciting a set of approved prayers or making charitable contributions. The 1999 “Manual of Indulgences” provides guidelines for church-sanctioned practices.

Protestant Christians view indulgences as neither biblical nor theologically defensible – in their view, only God can directly forgive sins.

Parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church sold their own version of certificates of indulgences well into the 20th century. Believed to be a Catholic corruption of its own theology, the Eastern Orthodox Church eradicated this practice throughout its ranks.

For some Catholics, to seek an indulgence is to participate in an ancient practice whose long history is rooted in the earliest centuries of the church. Other Catholics reject the doctrine of original sin or the doctrine of punishment for sins or both – for them, indulgences have little meaning.![]()

Myriam Renaud, DePaul University

Myriam Renaud, Affiliated Faculty of Bioethics, Religion, and Society, Department of Religious Studies, DePaul University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.