Mystique, minimalism and cataclysm: Cormac McCarthy’s fiction was a dark counter-narrative to American optimism.

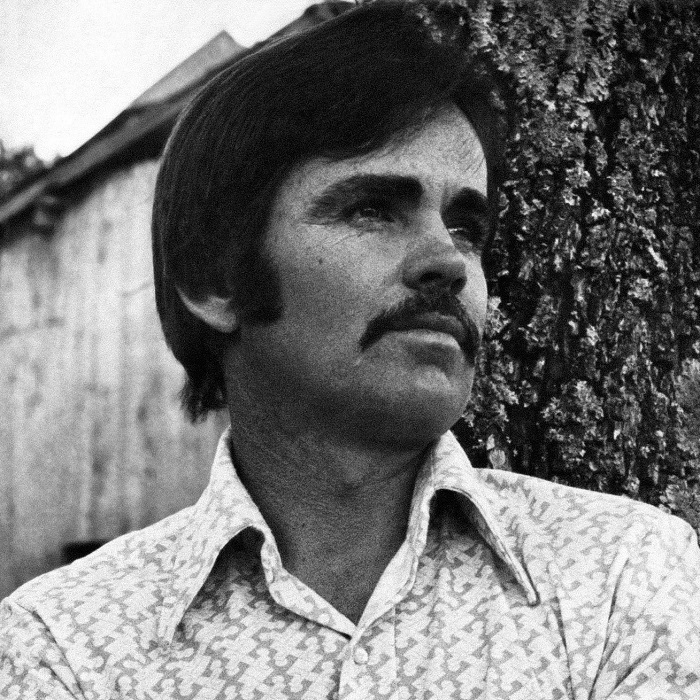

It is testimony to Cormac McCarthy’s reputation as a writer of dark and violent fictions that his publishers should explicitly have stated in their press release on Tuesday that his death was due to “natural causes”.

Normally the passing of a famous author at the age of 89 might be regarded as part of the natural cycle of things, but McCarthy’s frequent depictions of gruesome murder plots, and the judicious discussion of suicide in his most recent novel Stella Maris, perhaps induced Penguin Random House to emphasise how the author made his exit in a more conventional manner, garlanded by age and honours.

Given his own troubled personal history with alcohol, divorces and economic hardship during the early part of his career, such a consummation was never an entirely safe bet. Nevertheless, McCarthy eventually saw it through and he ended up a major American fiction writer, albeit a complex and often controversial figure whose works were typically unsettling.

‘Overpowering use of language’

Born Charles McCarthy into a comfortable Catholic family in Rhode Island in 1933, McCarthy subsequently took his pen-name “Cormac” as a memento of his Irish ancestry. He was brought up in Tennessee, with his early novels The Orchard Keeper (1965), Outer Dark (1968) and Suttree (1979) immersed in the cracker-barrel humour of the American Deep South.

While these works were respectfully received, they did not sell well, although they did bring McCarthy to the attention of Saul Bellow, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1976, who praised his “absolutely overpowering use of language”.

After being awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 1981, on the recommendation of Bellow, McCarthy travelled to Texas, New Mexico and other parts of the American Southwest. It was in this location that he found his most enduring and distinctive voice.

His most famous books, Blood Meridian (1985) and the Border Trilogy – All the Pretty Horses (1992), The Crossing (1994) and Cities of the Plain (1998) –characteristically represent questions of life and death in terms of violent cultural relations between the United States and Mexico. By recasting American history in the long shadow of its southern neighbour, McCarthy projects a memorable counter-narrative to the more conventional rhetoric of millennial optimism that has long been associated with American models of freedom and individualism.

The Road (2006), a bleak work of apocalyptic devastation that won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction the following year, also struck a public nerve because of the way it combined McCarthy’s customary scenarios of desolation with particular anxieties around the threat of climate change.

In McCarthy’s world, cataclysm is a normative state of affairs, with war and violence being primordial realities. Human behaviour through the ages is portrayed as being fundamentally insusceptible to change.

Though generally uncompromising in his artistic beliefs, McCarthy did reveal throughout his career a willingness to accommodate this sinister aesthetic to more accessible genres and formats. His bloodthirsty crime caper No Country for Old Men (2005), about a drug deal gone wrong, was made into a fine film by the Coen Brothers.

Intellectual innovation

More recently, McCarthy strove to integrate complex scientific material into narrative forms, with the ultimate result being a complementary pair of novels published last year: The Passenger, set primarily in New Orleans, and Stella Maris, which takes place at a psychiatric hospice in Wisconsin. McCarthy’s preoccupations in these final works turn upon the diminution of human agency and the fracturing of liberal consciousness through the coercive pressures of nuclear science, systems surveillance and big data.

But they address these sombre concerns in an often light-hearted and comic idiom: even secret service executions and personal self-harm become the stuff of self-deprecating comedy. “Suffering is a part of the human condition and must be borne,” says one character in The Passenger. “But misery is a choice.”

McCarthy was never an easy writer, and his oblique, multi-dimensional novels have become less fashionable in a Facebook era that prefers the attractions of personal stories and the allure of authenticity.

McCarthy’s art, by contrast, was shaped by the minimalism and stylistic impersonality of classic modernist writers such as Ernest Hemingway, along with the more abstract forms of post-humanism that he discussed with his scientific friends at the interdisciplinary Santa Fe institute, where he spent many of his later working years. He gave few interviews and was averse to the kind of self-publicity that has now become the norm in the world of literary marketing.

He did however retain, albeit on a more modest level, some of the mystique surrounding the charismatic or reclusive male author that was a familiar trope in 20th-century American literature, from Hemingway through to J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon.

McCarthy was also sometimes critiqued for his more limited representations of female characters, and in this way, along with many others, he could be seen as a traditional American Western writer.

It would, though, be wrong to categorise McCarthy’s achievement too narrowly. Though generally regarded as pessimistic, McCarthy’s texts also explore in intellectually innovative ways interconnections and tensions between white Protestant and Hispanic Catholic cultures in America. They also trace crossovers between humans and animals, social systems and the environment and, perhaps most significantly, rationality and its failures or ontological limitations.

The Crossing, the title of the second book in McCarthy’s Border Trilogy, might in this sense stand as an epitome of his oeuvre as a whole, which probes points of conjunction and disjunction across the American cultural terrain.

His novels will last as long as American literature itself lasts, though in this era of digital technology, as McCarthy himself with his mordant sense of humour would no doubt have chucklingly acknowledged, the extent of that lifespan is itself an open question.![]()

Paul Giles, Professor of English, Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, ACU, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.