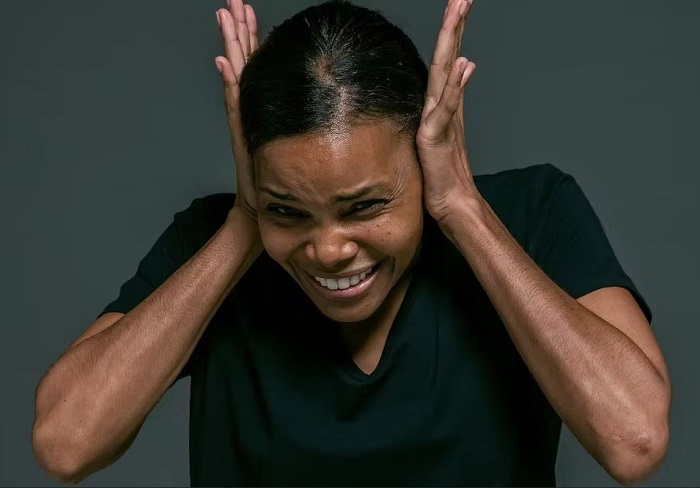

Hearing voices? You’re not alone.

From the little voice telling us we’re no good to the one offering advice, the experience of hearing voices is more common than you might think. It is estimated that 13.2% of the adult general population are subject to it, yet this experience still carries much stigma. Whom can you turn to when you’re no longer alone in your head?

For several decades now, the international Hearing Voices Movement (HVM) has been campaigning to improve the way this condition is perceived. Two recent studies conducted at the University of Lorraine in eastern France have assessed how its support groups have impacted the French health care system.

Changing textbooks

You’re hearing voices and in one fell swoop, the gavel falls: you’re mad. How could it be otherwise? You don’t need a shrink to say so. Our entire culture teaches us that the ego must remain master of its own house.

In psychiatry, hearing voices in the absence of external inputs is equated with hallucination, a clear expression of psychosis. Until recently, the mere symptom of voices conversing with each other was enough to warrant a diagnosis of schizophrenia. But even psychiatric textbooks are changing.

In addition to psychosis, which is sometimes diagnosed, such experiences occur spontaneously in unusual states of consciousness – for example, bereavement or trauma. The voices are often accompanied by paranormal experiences such as visions or messages. What would happen to Joan of Arc if she consulted a psychiatrist in 2023?

Less lonely together

Researchers now differentiate the experience of hearing voices from our distressed interpretations of them. Since the 1980s, a growing number of people have confessed to “hearing voices”.

All have managed to tap into a range of resources to deal with their experiences, without necessarily turning to psychiatry. By coming together, first in the Netherlands and then as an international movement, they realized that they possessed “experiential knowledge” that could help others like them find help and reverse the stigma they were suffering.

Some clinicians and researchers have backed this shift, whose watchword is “nothing about us without us”. Out with the accoustico-verbal hallucinations, in with the voices. The change in vocabulary is just one indication of the overall change in perspective, against the backdrop of a growing demand for health democracy.

Inclusive change

The movement “campaigns to drop models that pathologise these experiences,” says Magali Molinié, a psychologist and academic at the universities of Paris 8 and Cornell, who in 2011 co-founded the French Network on Voice Understanding. Its members prefer to consider that voices are real, carry meaning and links to trauma – even if opinions differ as to their explanations.

Among the alternatives promoted by the movement are Hearing Voices Groups (HVG). There are 180 in the United Kingdom alone, and they can now be found in 30 countries.

These self-help groups have no stated therapeutic aim. Instead, they act as a micro-society, where members can safely open up on their experiences and the events to which they are linked. It’s all part of the trend toward health care patient and provider empowerment, which has been recommended by the World Health Organisation.

The groups’ effectiveness

Each HVG has its own way of working and its own personality. How can we assess their advantages and disadvantages? A questionnaire designed jointly with English voice hearers has been adapted into French. The study compared the effects of HVGs with those of ordinary therapeutic groups. As the study took place during the Covid-19 pandemic, the groups ran slowly and only 20 of the 50 in France completed the study. However, the results were positive.

In particular, participants reported feeling better about themselves, more hopeful, less lonely and anxious and happier overall. The groups provided them with support that they had not been able to find elsewhere, as well as useful information to help them make sense of their experiences. Most of them now feel able to help other voice hearers in their turn. One participant even compared the setting to “Alcoholics Anonymous for schizophrenics”. Although this was not the aim, voice hearing even decreased for seven of the participants.

Are such positive reports enough to recommend such groups?

Different methods, similar results

The total satisfaction score was 74%. In parallel, a 14-person control group underwent meta-cognitive training, a method aimed at helping people with psychosis become more aware of thinking patterns contributing to their symptoms. Strikingly, their satisfaction score was also 74.5%. This indicates that HVGs are perceived to be as effective as scientifically proven practices.

HVGs hold the advantage of attracting people who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis or who do not fully accept it. In the absence of such spaces, these hearers would be more likely to bypass the medical-psychological circuit in favor of unconventional and poorly regulated forms of care, such as mediums who interpret voices as a gift of communication with the dead.

Ultimately, HVGs’ value lies not so much in their ability to replace existing treatments as to complement them.

In the minds of carers

As for HVGs’ integration within psychiatry, our research shows the field can do better. Surveying 79 staff from French mental health institutions, the second study confirmed the medical and caring personnel largely views them positively.

However, there are mismatches between what HVGs are and how professionals perceive them. There is an unhelpful tendency to reduce them to just another medical service, of little use in terms of symptom reduction, indicated only for psychotic patients who hear voices.

The more professionals familiarize ourselves with these structures, the more they stand to free themselves from such stereotypes. Through new eyes, yesterday’s madman becomes a fully fledged citizen.

For those interested in learning more about this issue, the 14th World Intervoice Conference will be held in Paris on 26 and 27 October 2023.![]()

Renaud Evrard, Université de Lorraine and Arthur Braun, Université de Lorraine

Renaud Evrard, Maître de conférences en psychologie, Université de Lorraine and Arthur Braun, Psychologue clinicien, doctorant en psychologie clinique, Université de Lorraine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.